Battle of Waterloo

| Battle of Waterloo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Waterloo campaign | |||||||

The Battle of Waterloo, by William Sadler II | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

72,000–73,000[a]

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

26,000–27,000[nb 5]

15,000 deserted after the battle[12] 220 guns lost[8] |

Total: 24,000[13][nb 7] Wellington's army: 17,000 killed, wounded, or missing[13][nb 8]

Blücher's army: 6,604–7,000[f]

| ||||||

| Both sides: 7,000 horses killed | |||||||

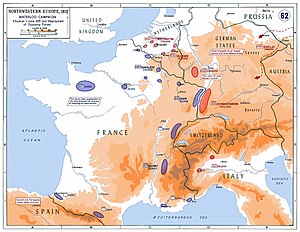

The Battle of Waterloo (Dutch: [ˈʋaːtərloː] ) was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium), marking the end of the Napoleonic Wars. A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two armies of the Seventh Coalition. One of these was a British-led force with units from the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Hanover, Brunswick, and Nassau, under the command of the Duke of Wellington (often referred to as the Anglo-allied army or Wellington's army). The other comprised three corps (the 1st, 2nd and 4th corps) of the Prussian army under Field Marshal Blücher; a fourth corps (the 3rd) of this army fought at the Battle of Wavre on the same day. The battle was known contemporarily as the Battle of Mont Saint-Jean in France (after the hamlet of Mont-Saint-Jean) and La Belle Alliance in Prussia ("the Beautiful Alliance"; after the inn of La Belle Alliance).[15]

Upon Napoleon's return to power in March 1815 (beginning the Hundred Days), many states that had previously opposed him formed the Seventh Coalition and hurriedly mobilised their armies. Wellington's and Blücher's armies were cantoned close to the northeastern border of France. Napoleon planned to attack them separately, before they could link up and invade France with other members of the coalition.

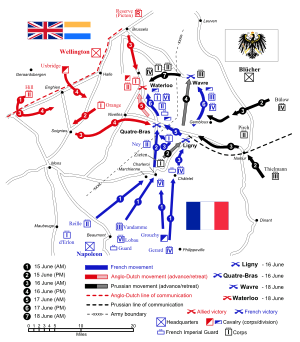

On 16 June, Napoleon successfully attacked the bulk of the Prussian army at the Battle of Ligny with his main force, while a small portion of the French army contested the Battle of Quatre Bras to prevent the Anglo-allied army from reinforcing the Prussians. The Anglo-allied army held their ground at Quatre Bras, and on the 17th, the Prussians withdrew from Ligny in good order, while Wellington then withdrew in parallel with the Prussians northward to Waterloo on 17 June. Napoleon sent a third of his forces to pursue the Prussians, which resulted in the separate Battle of Wavre with the Prussian rear-guard on 18–19 June and prevented that French force from participating at Waterloo.

Upon learning that the Prussian Army was able to support him, Wellington decided to offer battle on the Mont-Saint-Jean[16] escarpment across the Brussels Road, near the village of Waterloo. Here he withstood repeated attacks by the French throughout the afternoon of 18 June,[17] and was eventually aided by the progressively arriving 50,000 Prussians who attacked the French flank and inflicted heavy casualties. In the evening, Napoleon assaulted the Anglo-allied line with his last reserves, the senior infantry battalions of the Imperial Guard. With the Prussians breaking through on the French right flank, the Anglo-allied army repulsed the Imperial Guard, and the French army was routed.

Waterloo was the decisive engagement of the Waterloo campaign and Napoleon's last. It was also the second bloodiest single day battle of the Napoleonic Wars, after Borodino. According to Wellington, the battle was "the nearest-run thing you ever saw in your life".[18] Napoleon abdicated four days later, and coalition forces entered Paris on 7 July. The defeat at Waterloo marked the end of Napoleon's Hundred Days return from exile. It precipitated Napoleon's second and definitive abdication as Emperor of the French, and ended the First French Empire. It set a historical milestone between serial European wars and decades of relative peace, often referred to as the Pax Britannica. In popular culture, the phrase "meeting one's Waterloo" has become an expression for someone suffering a final defeat.

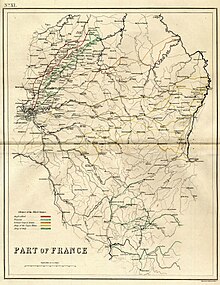

The battlefield is located in the Belgian municipalities of Braine-l'Alleud and Lasne,[19] about 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) south of Brussels, and about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from the town of Waterloo. The site of the battlefield today is dominated by the monument of the Lion's Mound, a large artificial hill constructed from earth taken from the battlefield itself, but the topography of the battlefield near the mound has not been preserved.

Prelude

On 13 March 1815, six days before Napoleon reached Paris, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared him an outlaw.[20] Four days later, the United Kingdom, Russia, Austria, and Prussia mobilised armies to defeat Napoleon.[21] Critically outnumbered, Napoleon knew that once his attempts at dissuading one or more members of the Seventh Coalition from invading France had failed, his only chance of remaining in power was to attack before the coalition mobilised.[22]

Had Napoleon succeeded in destroying the existing coalition forces south of Brussels before they were reinforced, he might have been able to drive the British back to the sea and knock the Prussians out of the war. Crucially, this would have bought him time to recruit and train more men before turning his armies against the Austrians and Russians.[23][24]

An additional consideration for Napoleon was that a French victory might cause French-speaking sympathisers in Belgium to launch a friendly revolution. Also, coalition troops in Belgium were largely second line, as many units were of dubious quality and loyalty.[25][26]

The initial dispositions of Wellington, the British commander, were intended to counter the threat of Napoleon enveloping the Coalition armies by moving through Mons to the south-west of Brussels.[27] This would have pushed Wellington closer to the Prussian forces, led by Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, but might have cut Wellington's communications with his base at Ostend. In order to delay Wellington's deployment, Napoleon spread false intelligence which suggested that Wellington's supply chain from the channel ports would be cut.[28]

By June, Napoleon had raised a total army strength of about 300,000 men. The force at his disposal at Waterloo was less than one third that size, but the rank and file were mostly loyal and experienced soldiers.[29] Napoleon divided his army into a left wing commanded by Marshal Ney, a right wing commanded by Marshal Grouchy and a reserve under his command (although all three elements remained close enough to support one another). Crossing the frontier near Charleroi before dawn on 15 June, the French rapidly overran Coalition outposts, securing Napoleon's "central position" between Wellington's and Blücher's armies. He hoped this would prevent them from combining, and he would be able to destroy first the Prussian army, then Wellington's.[30][31][32][33]

Only very late on the night of 15 June was Wellington certain that the Charleroi attack was the main French thrust. In the early hours of 16 June, at the Duchess of Richmond's ball in Brussels, he received a dispatch from the Prince of Orange and was shocked by the speed of Napoleon's advance. He hastily ordered his army to concentrate on Quatre Bras, where the Prince of Orange, with the brigade of Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, was holding a tenuous position against the soldiers of Ney's left wing. Prince Bernhard and General Perponcher were by all accounts better informed of the French advance than other allied officials and their later initiatives to hold the crossroads proved vital for the outcome. General Constant de Rebeque, commander of one of the Dutch divisions, disobeyed Wellington's orders to march to his previous chosen concentration area around Nivelles, and decided to hold the crossroads and send urgent messages to the prince and Perponcher. This fact shows how little Wellington believed in a fast French advance towards Brussels. He did not believe in recent intelligence given to him by General Dörnberg, one of his intelligence officials warning him of numerous French outposts south of Charleroi as well as some reports sent by the intelligence of the Prussian 1st corps. Had these two generals obeyed his orders, Quatre-Bras in all probability would have fallen to the French giving them time to support Napoleon's attack on the Prussians in the Sombreffe area via the fast, cobbled road, and the history of the campaign would have been significantly different.[34][35]

Ney's orders were to secure the crossroads of Quatre Bras so that he could later swing east and reinforce Napoleon if necessary. Ney found the crossroads lightly held by the Prince of Orange, who repelled Ney's initial attacks but was gradually driven back by overwhelming numbers of French troops in the Battle of Quatre Bras. First reinforcements, and then Wellington arrived. He took command and drove Ney back, securing the crossroads by early evening, too late to send help to the Prussians, who had already been defeated.[36][31][37]

Meanwhile, on 16 June, Napoleon attacked and defeated Blücher at the Battle of Ligny, using part of the reserve and the right wing of his army. The Prussian centre gave way under heavy French assaults, but the flanks held their ground. The Prussian retreat from Ligny went uninterrupted and seemingly unnoticed by the French. The bulk of their rearguard units held their positions until about midnight, and some elements did not move out until the following morning, ignored by the French.[38][39]

Crucially, the Prussians did not retreat to the east, along their own lines of communication. Instead, they, too, fell back northwards parallel to Wellington's line of march, still within supporting distance and in communication with him throughout. The Prussians rallied on Bülow's IV Corps, which had not been engaged at Ligny and was in a strong position south of Wavre.[40]

With the Prussian retreat from Ligny, Wellington's position at Quatre Bras was untenable. The next day he withdrew northwards, to a defensive position that he had reconnoitred the previous year—the low ridge of Mont-Saint-Jean, south of the village of Waterloo and the Sonian Forest.[41]

Napoleon, with the reserves, made a late start on 17 June and joined Ney at Quatre Bras at 13:00 to attack Wellington's army but found the position empty. The French pursued Wellington's retreating army to Waterloo; however, due to bad weather, mud and the head start that Napoleon's tardy advance had allowed Wellington, there was no substantial engagement, apart from a cavalry action at Genappe.[42][43]

Before leaving Ligny, Napoleon had ordered Grouchy, who commanded the right wing, to follow the retreating Prussians with 33,000 men. A late start, uncertainty about the direction the Prussians had taken, and the vagueness of the orders given to him meant that Grouchy was too late to prevent the Prussian army reaching Wavre, from where it could march to support Wellington. More importantly, the heavily outnumbered Prussian rearguard was able to use the River Dyle to fight a savage and prolonged action to delay Grouchy. Napoleon would get this information from Grouchy on the early morning of 18 June at a nearby farmhouse, La Caillou, where he was staying for the night; he responded to the message in mid-day.[44][45][43][46]

As 17 June drew to a close, Wellington's army had arrived at its position at Waterloo, with the main body of Napoleon's army in pursuit. Blücher's army was gathering in and around Wavre, around 8 miles (13 km) to the east of the town. Early the next morning, Wellington received an assurance from Blücher that the Prussian army would support him. He decided to hold his ground and give battle.[47][43]

Armies

Three armies participated in the battle: Napoleon's Armée du Nord, a multinational army under Wellington, and a Prussian army under General Blücher.

The French army of around 74,500 consisted of 54,014 infantry, 15,830 cavalry, and 8,775 artilleries with 254 guns.[48][49] Napoleon had used conscription to fill the ranks of the French army throughout his rule, but he did not conscript men for the 1815 campaign. His troops were mainly veterans with considerable experience and a fierce devotion to their Emperor.[50] The cavalry in particular was both numerous and formidable, and included fourteen regiments of armoured heavy cavalry, and seven of highly versatile lancers who were armed with lances, sabres and firearms.[51][52][53]

However, as the army took shape, French officers were allocated to units as they presented themselves for duty, so that many units were commanded by officers the soldiers did not know, and often did not trust. Crucially, some of these officers had little experience in working together as a unified force, so that support for other units was often not given.[54][55]

The French were forced to march through rain and black coal-dust mud to reach Waterloo, and then to contend with mud and rain as they slept in the open.[56] Little food was available, but nevertheless the veteran soldiers were fiercely loyal to Napoleon.[54][57]

In December 1814, the British Army had been reduced by 47,000 men.[58] This was largely achieved by the disbandment of the second battalion of 22 infantry regiments.[59] Wellington later said that he had "an infamous army, very weak and ill-equipped, and a very inexperienced Staff".[60] His troops consisted of 74,326 men: 53,607 infantry, 13,400 cavalry, and 5,596 artillery with 156 guns plus engineers and staff.[61] Of these, 27,985 (38%) were British, with another 7,686 (10%) from the King's German Legion (KGL). All of the British Army troops were regular soldiers, and the majority of them had served in the Peninsula. Of the 23 British line infantry regiments in action, only four (the 14th, 33rd, 69th, and 73rd Foot) had not served in the Peninsula, and a similar level of experience was to be found in the British cavalry and artillery. [citation needed] Chandler asserts that most of the British veterans of the Peninsular War were being transported to North America to fight in the War of 1812.[62] In addition, there were 21,035 (28.3%) Dutch-Belgian and Nassauer troops, 11,496 (15.5%) from Hanover and 6,124 (8.2%) from Brunswick.[63]

Many of the troops in the Coalition armies were inexperienced.[g][h] The Dutch army had been re-established in 1815, following the earlier defeat of Napoleon. With the exception of the British and some men from Hanover and Brunswick who had fought with the British army in Spain, many of the professional soldiers in the Coalition armies had spent some of their time in the French army or in armies allied to the Napoleonic regime. The historian Alessandro Barbero states that in this heterogeneous army the difference between British and foreign troops did not prove significant under fire.[64]

Wellington was also acutely short of heavy cavalry, having only seven British and three Dutch regiments. The Duke of York imposed many of his staff officers on Wellington, including his second-in-command, the Earl of Uxbridge. Uxbridge commanded the cavalry and had carte blanche from Wellington to commit these forces at his discretion. Wellington stationed a further 17,000 troops at Halle, 8 miles (13 km) away to the west. They were mostly composed of Dutch troops under the Prince of Orange's younger brother, Prince Frederick of the Netherlands. They were placed as a guard against a wide flanking movement and also to act as a rearguard if Wellington was forced to retreat towards Antwerp and the coast.[65][i]

The Prussian army was in the throes of reorganisation. In 1815, the former Reserve regiments, Legions, and Freikorps volunteer formations from the wars of 1813–1814 were in the process of being absorbed into the line, along with many Landwehr (militia) regiments. The Landwehr were mostly untrained and unequipped when they arrived in Belgium. The Prussian cavalry were in a similar state.[66] Its artillery was also reorganising and did not give its best performance—guns and equipment continued to arrive during and after the battle.[67]

Offsetting these handicaps, the Prussian army had excellent and professional leadership in its general staff. These officers came from four schools developed for this purpose and thus worked to a common standard of training. This system was in marked contrast to the conflicting, vague orders issued by the French army. This staff system ensured that before Ligny, three-quarters of the Prussian army had concentrated for battle with 24 hours' notice.[67]

After Ligny, the Prussian army, although defeated, was able to realign its supply train, reorganise itself, and intervene decisively on the Waterloo battlefield within 48 hours.[67] Two-and-a-half Prussian army corps, or 48,000 men, were engaged at Waterloo; two brigades under Bülow, commander of IV Corps, attacked Lobau at 16:30, while Zieten's I Corps and parts of Pirch I's II Corps engaged at about 18:00.[68]

Battlefield

The Waterloo position chosen by Wellington was a strong one. It consisted of a long ridge running east–west, perpendicular to, and bisected by, the main road to Brussels. Along the crest of the ridge ran the Ohain road, a deep sunken lane. Near the crossroads with the Brussels road was a large elm tree that was roughly in the centre of Wellington's position and served as his command post for much of the day. Wellington deployed his infantry in a line just behind the crest of the ridge following the Ohain road.[69]

Using the reverse slope, as he had many times previously, Wellington concealed his strength from the French, with the exception of his skirmishers and artillery.[69] The length of front of the battlefield was also relatively short at 2.5 miles (4 km). This allowed Wellington to draw up his forces in depth, which he did in the centre and on the right, all the way towards the village of Braine-l'Alleud, in the expectation that the Prussians would reinforce his left during the day.[70]

In front of the ridge, there were three positions that could be fortified. On the extreme right were the château, garden, and orchard of Hougoumont. This was a large and well-built country house, initially hidden in trees. The house faced north along a sunken, covered lane (usually described by the British as "the hollow-way") along which it could be supplied. On the extreme left was the hamlet of Papelotte.[71]

Both Hougoumont and Papelotte were fortified and garrisoned, and thus anchored Wellington's flanks securely. Papelotte also commanded the road to Wavre that the Prussians would use to send reinforcements to Wellington's position. On the western side of the main road, and in front of the rest of Wellington's line, was the farmhouse and orchard of La Haye Sainte, which was garrisoned with 400 light infantry of the King's German Legion.[71] On the opposite side of the road was a disused sand quarry, where the 95th Rifles were posted as sharpshooters.[72]

Wellington's forces positioning presented a formidable challenge to any attacking force. Any attempt to turn Wellington's right would entail taking the entrenched Hougoumont position. Any attack on his right centre would mean the attackers would have to march between enfilading fire from Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte. On the left, any attack would also be enfiladed by fire from La Haye Sainte and its adjoining sandpit, and any attempt at turning the left flank would entail fighting through the lanes and hedgerows surrounding Papelotte and the other garrisoned buildings on that flank, and some very wet ground in the Smohain defile.[73]

The French army formed on the slopes of another ridge to the south. Napoleon could not see Wellington's positions, so he drew his forces up symmetrically about the Brussels road. On the right was I Corps under d'Erlon with 16,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry, plus a cavalry reserve of 4,700. On the left was II Corps under Reille with 13,000 infantry, and 1,300 cavalry, and a cavalry reserve of 4,600. In the centre about the road south of the inn La Belle Alliance were a reserve including Lobau's VI Corps with 6,000 men, the 13,000 infantry of the Imperial Guard, and a cavalry reserve of 2,000.[74]

In the right rear of the French position was the substantial village of Plancenoit, and at the extreme right, the Bois de Paris wood. Napoleon initially commanded the battle from Rossomme farm, where he could see the entire battlefield, but moved to a position near La Belle Alliance early in the afternoon. Command on the battlefield (which was largely hidden from his view) was delegated to Ney.[75]

Battle

Preparation

Wellington rose at around 02:00 or 03:00 on 18 June, and wrote letters until dawn. He had earlier written to Blücher confirming that he would give battle at Mont-Saint-Jean if Blücher could provide him with at least one corps; otherwise he would retreat towards Brussels. At a late-night council, Blücher's chief of staff, August Neidhardt von Gneisenau, had been distrustful of Wellington's strategy, but Blücher persuaded him that they should march to join Wellington's army. In the morning Wellington duly received a reply from Blücher, promising to support him with three corps.[76]

From 06:00 Wellington was in the field supervising the deployment of his forces. At Wavre, the Prussian IV Corps under Bülow was designated to lead the march to Waterloo as it was in the best shape, not having been involved in the Battle of Ligny. Although they had not taken casualties, IV Corps had been marching for two days, covering the retreat of the three other corps of the Prussian army from the battlefield of Ligny. They had been posted farthest away from the battlefield, and progress was very slow.[77][78]

The roads were in poor condition after the night's heavy rain, and Bülow's men had to pass through the congested streets of Wavre and move 88 artillery pieces. Matters were not helped when a fire broke out in Wavre, blocking several streets along Bülow's intended route. As a result, the last part of the corps left at 10:00, six hours after the leading elements had moved out towards Waterloo. Bülow's men were followed to Waterloo first by I Corps and then by II Corps.[77][78]

Napoleon breakfasted off silver plate at Le Caillou, the house where he had spent the night. When Soult suggested that Grouchy should be recalled to join the main force, Napoleon said, "Just because you have all been beaten by Wellington, you think he's a good general. I tell you Wellington is a bad general, the English are bad troops, and this affair is nothing more than eating breakfast".[79][78]

Napoleon's seemingly dismissive remark may have been strategic, given his maxim "in war, morale is everything". He had acted similarly in the past, and on the morning of the battle of Waterloo may have been responding to the pessimism and objections of his chief of staff and senior generals.[80]

Later on, being told by his brother, Jerome, of some gossip overheard by a waiter between British officers at lunch at the King of Spain inn in Genappe that the Prussians were to march over from Wavre, Napoleon declared that the Prussians would need at least two days to recover and would be dealt with by Grouchy.[81] Surprisingly, Jerome's overheard gossip aside, the French commanders present at the pre-battle conference at Le Caillou had no information about the alarming proximity of the Prussians and did not suspect that Blücher's men would start erupting onto the field of battle in great numbers just five hours later.[82]

Napoleon had delayed the start of the battle owing to the sodden ground, which would have made manoeuvring cavalry and artillery difficult. In addition, many of his forces had bivouacked well to the south of La Belle Alliance. At 10:00, in response to a dispatch he had received from Grouchy six hours earlier, he sent a reply telling Grouchy to "head for Wavre [to Grouchy's north] in order to draw near to us [to the west of Grouchy]" and then "push before him" the Prussians to arrive at Waterloo "as soon as possible".[83][78]

At 11:00, Napoleon drafted his general order: Reille's Corps on the left and d'Erlon's Corps to the right were to attack the village of Mont-Saint-Jean and keep abreast of one another. This order assumed Wellington's battle-line was in the village, rather than at the more forward position on the ridge.[84] To enable this, Jerome's division would make an initial attack on Hougoumont, which Napoleon expected would draw in Wellington's reserves,[85] since its loss would threaten his communications with the sea. A grande batterie of the reserve artillery of I, II, and VI Corps was to then bombard the centre of Wellington's position from about 13:00. D'Erlon's corps would then attack Wellington's left, break through, and roll up his line from east to west. In his memoirs, Napoleon wrote that his intention was to separate Wellington's army from the Prussians and drive it back towards the sea.[86]

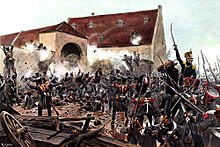

Hougoumont

Historian Andrew Roberts notes that "It is a curious fact about the Battle of Waterloo that no one is absolutely certain when it actually began".[88] Wellington recorded in his dispatches that at "about ten o'clock [Napoleon] commenced a furious attack upon our post at Hougoumont".[89] Other sources state that the attack began around 11:30.[j] The house and its immediate environs were defended by four light companies of Guards, and the wood and park by Hanoverian Jäger and the 1/2nd Nassau.[k][90]

The initial attack by Pierre François Bauduin's brigade emptied the wood and park, but was driven back by heavy British artillery fire, and cost Bauduin his life. As the British guns were distracted by a duel with French artillery, a second attack by Soye's brigade and what had been Bauduin's succeeded in reaching the north gate of the house. Sous-Lieutenant Legros, a French officer, broke the gate open with an axe, and some French troops managed to enter the courtyard.[91] The Coldstream Guards and the Scots Guards arrived to support the defence. There was a fierce melee, and the British managed to close the gate on the French troops streaming in. The Frenchmen trapped in the courtyard were all killed.

Fighting continued around Hougoumont all afternoon. Its surroundings were heavily invested by French light infantry, and coordinated attacks were made against the troops behind Hougoumont. Wellington's army defended the house and the hollow way running north from it. In the afternoon, Napoleon personally ordered the house to be shelled to set it on fire,[l] resulting in the destruction of all but the chapel. Du Plat's brigade of the King's German Legion was brought forward to defend the hollow way, which they had to do without senior officers. Eventually they were relieved by the 71st Highlanders, a British infantry regiment. Adam's brigade was further reinforced by Hugh Halkett's 3rd Hanoverian Brigade, and successfully repulsed further infantry and cavalry attacks sent by Reille. Hougoumont held out until the end of the battle.

I had occupied that post with a detachment from General Byng's brigade of Guards, which was in position in its rear; and it was some time under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel MacDonald, and afterwards of Colonel Home; and I am happy to add that it was maintained, throughout the day, with the utmost gallantry by these brave troops, notwithstanding the repeated efforts of large bodies of the enemy to obtain possession of it.

— Wellington.[92]

When I reached Lloyd's abandoned guns, I stood near them for about a minute to contemplate the scene: it was grand beyond description. Hougoumont and its wood sent up a broad flame through the dark masses of smoke that overhung the field; beneath this cloud the French were indistinctly visible. Here a waving mass of long red feathers could be seen; there, gleams as from a sheet of steel showed that the cuirassiers were moving; 400 cannon were belching forth fire and death on every side; the roaring and shouting were indistinguishably commixed—together they gave me an idea of a labouring volcano. Bodies of infantry and cavalry were pouring down on us, and it was time to leave contemplation, so I moved towards our columns, which were standing up in square.

— Major Macready, Light Division, 30th British Regiment, Halkett's brigade.[93]

The fighting at Hougoumont has often been characterised as a diversionary attack to draw in Wellington's reserves which escalated into an all-day battle and drew in French reserves instead.[94] In fact there is a good case to believe that both Napoleon and Wellington thought that holding Hougoumont was key to winning the battle. Hougoumont was a part of the battlefield that Napoleon could see clearly,[95] and he continued to direct resources towards it and its surroundings all afternoon (33 battalions in all, 14,000 troops). Similarly, though the house never contained a large number of troops, Wellington devoted 21 battalions (12,000 troops) over the course of the afternoon in keeping the hollow way open to allow fresh troops and ammunition to reach the buildings. He moved several artillery batteries from his hard-pressed centre to support Hougoumont,[96] and later stated that "the success of the battle turned upon closing the gates at Hougoumont".[97] Much like the fight for Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg in the US Civil War some fifty years later, the struggle for Hougoumont became the key battle within the battle. Hougoumont proved to be decisive terrain.

The Grand Battery starts its bombardment

The 80 guns of Napoleon's grande batterie drew up in the centre. These opened fire at 11:50, according to Lord Hill (commander of the Anglo-allied II Corps),[m] while other sources put the time between noon and 13:30.[98] The grande batterie was too far back to aim accurately, and the only other troops they could see were skirmishers of the regiments of Kempt and Pack, and Perponcher's 2nd Dutch division (the others were employing Wellington's characteristic "reverse slope defence").[99][n]

The bombardment caused a large number of casualties. Although some projectiles buried themselves in the soft soil, most found their marks on the reverse slope of the ridge. The bombardment forced the cavalry of the Union Brigade (in third line) to move to its left, to reduce their casualty rate.[100]

Napoleon spots the Prussians

At about 13:15, Napoleon saw the first columns of Prussians around the village of Lasne-Chapelle-Saint-Lambert, 4 to 5 miles (6.4 to 8.0 km) away from his right flank—about three hours march for an army.[101] Napoleon's reaction was to have Marshal Soult send a message to Grouchy telling him to come towards the battlefield and attack the arriving Prussians.[102] Grouchy, however, had been executing Napoleon's previous orders to follow the Prussians "with your sword against his back" towards Wavre, and was by then too far away to reach Waterloo.[103]

Grouchy was advised by his subordinate, Gérard, to "march to the sound of the guns", but stuck to his orders and engaged the Prussian III Corps rearguard, under the command of Lieutenant-General Baron von Thielmann, at the Battle of Wavre. Moreover, Soult's letter ordering Grouchy to move quickly to join Napoleon and attack Bülow would not actually reach Grouchy until after 20:00.[103]

First French infantry attack

A little after 13:00, I Corps' attack began in large columns. Bernard Cornwell writes "[column] suggests an elongated formation with its narrow end aimed like a spear at the enemy line, while in truth it was much more like a brick advancing sideways and d'Erlon's assault was made up of four such bricks, each one a division of French infantry".[104] Each division, with one exception, was drawn up in huge masses, consisting of the eight or nine battalions of which they were formed, deployed, and placed in a column one behind the other, with only five paces interval between the battalions.[105]

The one exception was the 1st Division (led by Quiot, the commander of the 1st Brigade).[105] Its two brigades were formed in a similar manner, but side by side instead of behind one another. This was done because, being on the left of the four divisions, it was ordered to send one (Quiot's brigade) against the south and west of La Haye Sainte, while the other (Bourgeois') was to attack the eastern side of the same post.[105]

The divisions were to advance in echelon from the left at a distance of 400 paces apart—the 2nd Division (Donzelot's) on the right of Bourgeois' brigade, the 3rd Division (Marcognet's) next, and the 4th Division (Durutte's) on the right. They were led by Ney to the assault, each column having a front of about a hundred and sixty to two hundred files.[105]

The leftmost division advanced on the walled farmhouse compound La Haye Sainte. The farmhouse was defended by the King's German Legion. While one French battalion engaged the defenders from the front, the following battalions fanned out to either side and, with the support of several squadrons of cuirassiers, succeeded in isolating the farmhouse. The King's German Legion resolutely defended the farmhouse. Each time the French tried to scale the walls, the outnumbered Germans somehow held them off. The Prince of Orange saw that La Haye Sainte had been cut off and tried to reinforce it by sending forward the Hanoverian Lüneburg Battalion in line. Cuirassiers concealed in a fold in the ground caught and destroyed it in minutes and then rode on past La Haye Sainte, almost to the crest of the ridge, where they covered d'Erlon's left flank as his attack developed.[107]

At about 13:30, d'Erlon started to advance his three other divisions, some 14,000 men over a front of about 1,000 metres (1,100 yards), against Wellington's left wing. At the point they aimed for, they faced 6,000 men: the first line consisted of the 1st brigade (Van Bylandt's brigade) of the 2nd Netherlands Division, flanked by the British brigades of Kempt and Pack on either side. The second line consisted of British and Hanoverian troops under Sir Thomas Picton, who were lying down in dead ground behind the ridge. All had suffered badly at Quatre Bras. In addition, Bylandt's brigade had been ordered to deploy its skirmishers in the hollow road and on the forward slope. The rest of the brigade was lying down just behind the road.[o][p]

At the moment these skirmishers were rejoining their parent battalions, the brigade was ordered to its feet and started to return fire. On the left of the brigade, where the 7th Dutch Militia stood, a "few files were shot down and an opening in the line thus occurred".[108] The battalion had no reserves and was unable to close the gap.[t]

D'Erlon's men ascended the slope and advanced on the sunken road, Chemin d'Ohain, that ran from behind La Haye Sainte and continued east. It was lined on both sides by thick hedges, with Bylandt's brigade just across the road, while the British brigades had been lying down some 100 yards back from the road, Pack's to Bylandt's left and Kempt's to Bylandt's right. Kempt's 1,900 men were engaged by Bourgeois' brigade of 1,900 men of Quiot's division. In the centre, Donzelot's division had pushed back Bylandt's brigade.[109]

On the right of the French advance was Marcognet's division, led by Grenier's brigade, consisting of the 45e Régiment de Ligne and followed by the 25e Régiment de Ligne, somewhat less than 2,000 men, and behind them, Nogue's brigade of the 21e and 45e regiments. Opposing them on the other side of the road was Pack's 9th Brigade, consisting of the 44th Foot and three Scottish regiments: the Royal Scots, the 42nd Black Watch, and the 92nd Gordons, totalling something over 2,000 men. A very even fight between British and French infantry was about to occur.[109]

The French advance drove in the British skirmishers and reached the sunken road. As they did so, Pack's men stood up, formed into a four-deep line formation for fear of the French cavalry, advanced, and opened fire. However, a firefight had been anticipated and the French infantry had accordingly advanced in more linear formation. Now, fully deployed into line, they returned fire and successfully pressed the British troops; although the attack faltered at the centre, the line in front of d'Erlon's right started to crumble. Picton was killed shortly after ordering a counter-attack, and the British and Hanoverian troops also began to give way under the pressure of numbers.[110]

Pack's regiments, all four ranks deep, advanced to attack the French in the road but faltered and began to fire on the French instead of charging. The 42nd Black Watch halted at the hedge and the resulting fire-fight drove back the British 92nd Foot, while the leading French 45e Ligne burst through the hedge cheering. Along the sunken road, the French were forcing the Anglo-allies back, the British line was dispersing, and at two o'clock in the afternoon Napoleon was winning the Battle of Waterloo.[111]

Reports from Baron von Müffling, the Prussian liaison officer attached to Wellington's army, relate that, "After 3 o'clock the Duke's situation became critical, unless the succour of the Prussian army arrived soon".[112]

Charge of the British heavy cavalry

Our officers of cavalry have acquired a trick of galloping at everything. They never consider the situation, never think of manoeuvring before an enemy, and never keep back or provide a reserve.

— Wellington.[113]

At this crucial juncture, Uxbridge ordered his two brigades of British heavy cavalry—formed unseen behind the ridge—to charge in support of the hard-pressed infantry. The 1st Brigade, known as the Household Brigade, commanded by Major-General Lord Edward Somerset, consisted of guards regiments: the 1st and 2nd Life Guards, the Royal Horse Guards (the Blues), and the 1st (King's) Dragoon Guards. The 2nd Brigade, also known as the Union Brigade, commanded by Major-General Sir William Ponsonby, was so called as it consisted of an English (the 1st or The Royals), a Scottish (2nd Scots Greys), and an Irish (6th or Inniskilling) regiment of heavy dragoons.[114][115]

More than 20 years of warfare had eroded the numbers of suitable cavalry mounts available on the European continent; this resulted in the British heavy cavalry entering the 1815 campaign with the finest horses of any contemporary cavalry arm. British cavalry troopers also received excellent mounted swordsmanship training. They were, however, inferior to the French in manoeuvring in large formations, were cavalier in attitude, and, unlike the infantry, some units had scant experience of warfare.[113]

The Scots Greys, for example, had not been in action since 1795.[116] According to Wellington, though they were superior individual horsemen, they were inflexible and lacked tactical ability.[113] "I considered one squadron a match for two French, I didn't like to see four British opposed to four French: and as the numbers increased and order, of course, became more necessary I was the more unwilling to risk our men without having a superiority in numbers."[117]

The two brigades had a combined field strength of about 2,000 (2,651 official strength); they charged with the 47-year-old Uxbridge leading them and a very inadequate number of squadrons held in reserve.[118][u] There is evidence that Uxbridge gave an order, the morning of the battle, to all cavalry brigade commanders to commit their commands on their own initiative, as direct orders from himself might not always be forthcoming, and to "support movements to their front".[119] It appears that Uxbridge expected the brigades of Sir John Ormsby Vandeleur, Hussey Vivian, and the Dutch cavalry to provide support to the British heavies. Uxbridge later regretted leading the charge in person, saying "I committed a great mistake", when he should have been organising an adequate reserve to move forward in support.[120]

The Household Brigade crossed the crest of the Anglo-allied position and charged downhill. The cuirassiers guarding d'Erlon's left flank were still dispersed, and so were swept over the deeply sunken main road and then routed.[121][v]

The blows of the sabres on the cuirasses sounded like braziers at work.

— Lord Edward Somerset.[123]

Sir Walter Scott, in Paul's Letters to his Kinsfolk, described the following scene:

Sir John Elley, who led the charge of the heavy brigade, was [...] at one time surrounded by several of the cuirassiers; but, being a tall and uncommonly powerful man, completely master of his sword and horse, he cut his way out, leaving several of his assailants on the ground, marked with wounds, indicating the unusual strength of the arm which inflicted them. Indeed, had not the ghastly evidence remained on the field, many of the blows dealt upon this occasion would have seemed borrowed from the annals of knight-errantry [...]

Continuing their attack, the squadrons on the left of the Household Brigade then destroyed Aulard's brigade. Despite attempts to recall them, they continued past La Haye Sainte and found themselves at the bottom of the hill on blown horses facing Schmitz's brigade formed in squares.[124]

To their left, the Union Brigade suddenly swept through the infantry lines, giving rise to the legend that some of the 92nd Gordon Highland Regiment clung onto their stirrups and accompanied them into the charge.[w] From the centre leftwards, the Royal Dragoons destroyed Bourgeois' brigade, capturing the eagle of the 105e Ligne. The Inniskillings routed the other brigade of Quoit's division, and the Scots Greys came upon the lead French regiment, 45e Ligne, as it was still reforming after having crossed the sunken road and broken through the hedge row in pursuit of the British infantry. The Greys captured the eagle of the 45e Ligne[125] and overwhelmed Grenier's brigade. These would be the only two French eagles captured by the British during the battle.[126] On Wellington's extreme left, Durutte's division had time to form squares and fend off groups of Greys.

As with the Household Cavalry, the officers of the Royals and Inniskillings found it very difficult to rein back their troops, who lost all cohesion. Having taken casualties, and still trying to reorder themselves, the Scots Greys and the rest of the Union Brigade found themselves before the main French lines.[127] Their horses were blown, and they were still in disorder without any idea of what their next collective objective was. Some attacked nearby gun batteries of the Grande Battery.[128] Although the Greys had neither the time nor means to disable the cannon or carry them off, they put very many out of action as the gun crews were killed or fled the battlefield.[129] Sergeant Major Dickinson of the Greys stated that his regiment was rallied before going on to attack the French artillery: Hamilton, the regimental commander, rather than holding them back cried out to his men "Charge, charge the guns!"[130]

Napoleon promptly responded by ordering a counter-attack by the cuirassier brigades of Farine and Travers and Jaquinot's two Chevau-léger (lancer) regiments in the I Corps light cavalry division. Disorganized and milling about the bottom of the valley between Hougoumont and La Belle Alliance, the Scots Greys and the rest of the British heavy cavalry were taken by surprise by the countercharge of Milhaud's cuirassiers, joined by lancers from Baron Jaquinot's 1st Cavalry Division.[131]

As Ponsonby tried to rally his men against the French cuirassers, he was attacked by Jaquinot's lancers and captured. A nearby party of Scots Greys saw the capture and attempted to rescue their brigade commander. The French lancer who had captured Ponsonby killed him and then used his lance to kill three of the Scots Greys who had attempted the rescue.[127]

By the time Ponsonby died, the momentum had entirely returned in favour of the French. Milhaud's and Jaquinot's cavalrymen drove the Union Brigade from the valley. The result was very heavy losses for the British cavalry.[132][133] A countercharge, by British light dragoons under Major-General Vandeleur and Dutch–Belgian light dragoons and hussars under Major-General Ghigny on the left wing, and Dutch–Belgian carabiniers under Major-General Trip in the centre, repelled the French cavalry.[134]

All figures quoted for the losses of the cavalry brigades as a result of this charge are estimates, as casualties were only noted down after the day of the battle and were for the battle as a whole.[135][x] Some historians, Barbero for example,[136] believe the official rolls tend to overestimate the number of cavalrymen present in their squadrons on the field of battle and that the proportionate losses were, as a result, considerably higher than the numbers on paper might suggest.[y]

The Union Brigade lost heavily in both officers and men killed (including its commander, William Ponsonby, and Colonel Hamilton of the Scots Greys) and wounded. The 2nd Life Guards and the King's Dragoon Guards of the Household Brigade also lost heavily (with Colonel Fuller, commander of the King's DG, killed). However, the 1st Life Guards, on the extreme right of the charge, and the Blues, who formed a reserve, had kept their cohesion and consequently suffered significantly fewer casualties.[137][z] On the rolls the official, or paper strength, for both Brigades is given as 2,651 while Barbero and others estimate the actual strength at around 2,000[136][aa] and the official recorded losses for the two heavy cavalry brigades during the battle was 1,205 troopers and 1,303 horses.[114][ab]

Some historians, such as Chandler, Weller, Uffindell, and Corum, assert that the British heavy cavalry were destroyed as a viable force following their first, epic charge.[138][139] Barbero states that the Scots Greys were practically wiped out and that the other two regiments of the Union Brigade suffered comparable losses.[140] Other historians, such as Clark-Kennedy and Wood, citing British eyewitness accounts, describe the continuing role of the heavy cavalry after their charge. The heavy brigades, far from being ineffective, continued to provide valuable services. They countercharged French cavalry numerous times (both brigades),[141][142][143][144] halted a combined cavalry and infantry attack (Household Brigade only),[145][146][147] were used to bolster the morale of those units in their vicinity at times of crisis, and filled gaps in the Anglo-allied line caused by high casualties in infantry formations (both brigades).[148][149][150][151][152]

This service was rendered at a very high cost, as close combat with French cavalry, carbine fire, infantry musketry, and—more deadly than all of these—artillery fire steadily eroded the number of effectives in the two brigades.[ac] At 6 o'clock in the afternoon the whole Union Brigade could field only three squadrons, though these countercharged French cavalry, losing half their number in the process.[142] At the end of the fighting, the two brigades, by this time combined, could muster one squadron.[142][151][153]

Fourteen thousand French troops of d'Erlon's I Corps had been committed to this attack. The I Corps had been driven in rout back across the valley, costing Napoleon 3,000 casualties[154] including over 2,000 prisoners taken.[155] Also some valuable time was lost, as the charge had dispersed numerous units and it would take until 16:00 for d'Erlon's shaken corps to reform. And although elements of the Prussians now began to appear on the field to his right, Napoleon had already ordered Lobau's VI corps to move to the right flank to hold them back before d'Erlon's attack began.

The French cavalry attack

A little before 16:00, Ney noted an apparent exodus from Wellington's centre. He mistook the movement of casualties to the rear for the beginnings of a retreat, and sought to exploit it. Following the defeat of d'Erlon's Corps, Ney had few infantry reserves left, as most of the infantry had been committed either to the futile Hougoumont attack or to the defence of the French right. Ney therefore tried to break Wellington's centre with cavalry alone.[156] Initially, Milhaud's reserve cavalry corps of cuirassiers and Lefebvre-Desnoëttes' light cavalry division of the Imperial Guard, some 4,800 sabres, were committed. When these were repulsed, Kellermann's heavy cavalry corps and Guyot's heavy cavalry of the Guard were added to the massed assault, a total of around 9,000 cavalry in 67 squadrons.[157] When Napoleon saw the charge he said it was an hour too soon.[154]

Wellington's infantry responded by forming squares (hollow box-formations four ranks deep). Squares were much smaller than usually depicted in paintings of the battle—a 500-man battalion square would have been no more than 60 feet (18 m) in length on a side. Infantry squares that stood their ground were deadly to cavalry, as cavalry could not engage with soldiers behind a hedge of bayonets, but were themselves vulnerable to fire from the squares. Horses would not charge a square, nor could they be outflanked, but they were vulnerable to artillery or infantry. Wellington ordered his artillery crews to take shelter within the squares as the cavalry approached, and to return to their guns and resume fire as they retreated.[158][159]

Witnesses in the British infantry recorded 12 assaults.[160] However, due to the wide frontage of cavalry formations and the 950m space between Hougoumont and La Haie Sainte, any massed cavalry advance would, in reality, consist of a number of successive waves.[157] Kellermann, recognising the futility of the attacks, tried to reserve the elite carabinier brigade from joining in, but eventually Ney spotted them and insisted on their involvement.[161]

A British eyewitness of the first French cavalry attack, an officer in the Foot Guards, recorded his impressions very lucidly and somewhat poetically:

About four p.m., the enemy's artillery in front of us ceased firing all of a sudden, and we saw large masses of cavalry advance: not a man present who survived could have forgotten in after life the awful grandeur of that charge. You discovered at a distance what appeared to be an overwhelming, long moving line, which, ever advancing, glittered like a stormy wave of the sea when it catches the sunlight. On they came until they got near enough, whilst the very earth seemed to vibrate beneath the thundering tramp of the mounted host. One might suppose that nothing could have resisted the shock of this terrible moving mass. They were the famous cuirassiers, almost all old soldiers, who had distinguished themselves on most of the battlefields of Europe. In an almost incredibly short period they were within twenty yards of us, shouting "Vive l'Empereur!" The word of command, "Prepare to receive cavalry", had been given, every man in the front ranks knelt, and a wall bristling with steel, held together by steady hands, presented itself to the infuriated cuirassiers.

— Captain Rees Howell Gronow, Foot Guards.[162]

In essence this type of massed cavalry attack relied almost entirely on psychological shock for effect.[163] Close artillery support could disrupt infantry squares and allow cavalry to penetrate; at Waterloo, however, co-operation between the French cavalry and artillery was not impressive. The French artillery did not get close enough to the Anglo-allied infantry in sufficient numbers to be decisive.[164] Artillery fire between charges did produce mounting casualties, but most of this fire was at relatively long range and was often indirect, at targets beyond the ridge.[165]

If infantry being attacked held firm in their square defensive formations, and were not panicked, cavalry on their own could do very little damage to them. The French cavalry attacks were repeatedly repelled by the steadfast infantry squares, the harrying fire of British artillery as the French cavalry recoiled down the slopes to regroup, and the decisive countercharges of Wellington's light cavalry regiments, the Dutch heavy cavalry brigade, and the remaining effectives of the Household Cavalry.[165]

At least one artillery officer disobeyed Wellington's order to seek shelter in the adjacent squares during the charges. Captain Mercer, who commanded 'G' Troop, Royal Horse Artillery, thought the Brunswick troops on either side of him so shaky that he kept his battery of six nine-pounders in action against the cavalry throughout, to great effect.[165][ad]

I thus allowed them to advance unmolested until the head of the column might have been about fifty or sixty yards from us, and then gave the word, "Fire!" The effect was terrible. Nearly the whole leading rank fell at once; and the round shot, penetrating the column carried confusion throughout its extent ... the discharge of every gun was followed by a fall of men and horses like that of grass before the mower's scythe.

— Captain Cavalié Mercer, RHA.[166]

For reasons that remain unclear, no attempt was made to spike other Anglo-allied guns while they were in French possession. In line with Wellington's orders, gunners were able to return to their pieces and fire into the French cavalry as they withdrew after each attack. After numerous costly but fruitless attacks on the Mont-Saint-Jean ridge, the French cavalry was spent.[ae]

Their casualties cannot easily be estimated. Senior French cavalry officers, in particular the generals, experienced heavy losses. Four divisional commanders were wounded, nine brigadiers wounded, and one killed—testament to their courage and their habit of leading from the front.[161] Illustratively, Houssaye reports that the Grenadiers à Cheval numbered 796 of all ranks on 15 June, but just 462 on 19 June, while the Empress Dragoons lost 416 of 816 over the same period.[167] Overall, Guyot's Guard heavy cavalry division lost 47% of its strength.

Second French infantry attack

Eventually it became obvious, even to Ney, that cavalry alone were achieving little. Belatedly, he organised a combined-arms attack, using Bachelu's division and Tissot's regiment of Foy's division from Reille's II Corps (about 6,500 infantrymen) plus those French cavalry that remained in a fit state to fight. This assault was directed along much the same route as the previous heavy cavalry attacks (between Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte).[168] It was halted by a charge of the Household Brigade cavalry led by Uxbridge. The British cavalry were unable, however, to break the French infantry, and fell back with losses from musketry fire.[169]

Uxbridge recorded that he tried to lead the Dutch Carabiniers, under Major-General Trip, to renew the attack and that they refused to follow him. Other members of the British cavalry staff also commented on this occurrence.[170] However, there is no support for this incident in Dutch or Belgian sources,[ag] and Wellington wrote in his Dispatch to Secretary for War Bathurst on 19 June 1815 that General Trip had "conducted himself much to my satisfaction".[171] Uxbridge then ordered a charge by three squadrons of the 3rd Hussars of the King's German Legion. They broke through the French cavalry, but became hemmed in, were cut off and suffered severe losses.[172] Meanwhile, Bachelu's and Tissot's men and their cavalry supports were being hard hit by fire from artillery and from Adam's infantry brigade, and they eventually fell back.[168]

Although the French cavalry caused few direct casualties to Wellington's centre, artillery fire onto his infantry squares caused many. Wellington's cavalry, except for Sir John Vandeleur's and Sir Hussey Vivian's brigades on the far left, had all been committed to the fight, and had taken significant losses. The situation appeared so desperate that the Cumberland Hussars, the only Hanoverian cavalry regiment present, fled the field spreading alarm all the way to Brussels.[173][ah]

French capture of La Haye Sainte

At approximately the same time as Ney's combined-arms assault on the centre-right of Wellington's line, rallied elements of D'Erlon's I Corps, spearheaded by the 13th Légère, renewed the attack on La Haye Sainte and this time were successful, partly because the King's German Legion's ammunition ran out. However, the Germans had held the centre of the battlefield for almost the entire day, and this had stalled the French advance.[174][175]

With La Haye Sainte captured, Ney then moved skirmishers and horse artillery up towards Wellington's centre.[176] French artillery began to pulverise the infantry squares at short range with canister.[177] The 30th and 73rd Regiments suffered such heavy losses that they had to combine to form a viable square.[178]

The possession of La Haye Sainte by the French was a very dangerous incident. It uncovered the very centre of the Anglo-allied army, and established the enemy within 60 yards of that centre. The French lost no time in taking advantage of this, by pushing forward infantry supported by guns, which enabled them to maintain a most destructive fire upon Alten's left and Kempt's right ...

The success Napoleon needed to continue his offensive had occurred.[180] Ney was on the verge of breaking the Anglo-allied centre.[179]

Along with this artillery fire a multitude of French tirailleurs occupied the dominant positions behind La Haye Sainte and poured an effective fire into the squares. The situation for the Anglo-allies was now so dire that the 33rd Regiment's colours and all of Halkett's brigade's colours were sent to the rear for safety, described by historian Alessandro Barbero as, "... a measure that was without precedent".[181]

Wellington, noticing the slackening of fire from La Haye Sainte, with his staff rode closer to it. French skirmishers appeared around the building and fired on the British command as it struggled to get away through the hedgerow along the road. The Prince of Orange then ordered a single battalion of the KGL, the Fifth, to recapture the farm despite the obvious presence of enemy cavalry. Their Colonel, Christian Friedrich Wilhelm von Ompteda obeyed and led the battalion down the slope, chasing off some French skirmishers until French cuirassiers fell on his open flank, killed him, destroyed his battalion and took its colour.[180]

A Dutch–Belgian cavalry regiment ordered to charge retreated from the field instead, fired on by their own infantry. Merlen's Light Cavalry Brigade charged the French artillery taking position near La Haye Sainte but were shot to pieces and the brigade fell apart. The Netherlands Cavalry Division, Wellington's last cavalry reserve behind the centre having lost half their strength was now useless and the French cavalry, despite its losses, were masters of the field, compelling the Anglo-allied infantry to remain in square. More and more French artillery was brought forward.[182]

A French battery advanced to within 300 yards of the 1/1st Nassau square causing heavy casualties. When the Nassauers attempted to attack the battery they were ridden down by a squadron of cuirassiers. Yet another battery deployed on the flank of Mercer's battery and shot up its horses and limbers and pushed Mercer back. Mercer later recalled,

The rapidity and precision of this fire was quite appalling. Every shot almost took effect, and I certainly expected we should all be annihilated. ... The saddle-bags, in many instances were torn from horses' backs ... One shell I saw explode under the two finest wheel-horses in the troop down they dropped[182][183]

French tirailleurs occupied the dominant positions, especially one on a knoll overlooking the square of the 27th. Unable to break square to drive off the French infantry because of the presence of French cavalry and artillery, the 27th had to remain in that formation and endure the fire of the tirailleurs. That fire nearly annihilated the 27th Foot, the Inniskillings, who lost two thirds of their strength within that three or four hours.[184]

The banks on the road side, the garden wall, the knoll and sandpit swarmed with skirmishers, who seemed determined to keep down our fire in front; those behind the artificial bank seemed more intent upon destroying the 27th, who at this time, it may literally be said, were lying dead in square; their loss after La Haye Sainte had fallen was awful, without the satisfaction of having scarcely fired a shot, and many of our troops in rear of the ridge were similarly situated.

— Edward Cotton, 7th Hussars, [185]

During this time many of Wellington's generals and aides were killed or wounded including FitzRoy Somerset, Canning, de Lancey, Alten and Cooke.[186] The situation was now critical and Wellington, trapped in an infantry square and ignorant of events beyond it, was desperate for the arrival of help from the Prussians. He later wrote,

The time they occupied in approaching seemed interminable. Both they and my watch seemed to have stuck fast.[187]

Arrival of the Prussian IV Corps: Plancenoit

Night or the Prussians must come.

— Wellington.[187]

The Prussian IV Corps (Bülow's) was the first to arrive in strength. Bülow's objective was Plancenoit, which the Prussians intended to use as a springboard into the rear of the French positions. Blücher intended to secure his right upon the Châteaux Frichermont using the Bois de Paris road.[188] Blücher and Wellington had been exchanging communications since 10:00 and had agreed to this advance on Frichermont if Wellington's centre was under attack.[189][ai] General Bülow noted that the way to Plancenoit lay open and that the time was 16:30.[188]

At about this time, the Prussian 15th Brigade (Losthin's [de]) was sent to link up with the Nassauers of Wellington's left flank in the Frichermont-La Haie area, with the brigade's horse artillery battery and additional brigade artillery deployed to its left in support.[190] Napoleon sent Lobau's corps to stop the rest of Bülow's IV Corps proceeding to Plancenoit. The 15th Brigade threw Lobau's troops out of Frichermont with a determined bayonet charge, then proceeded up the Frichermont heights, battering French Chasseurs with 12-pounder artillery fire, and pushed on to Plancenoit. This sent Lobau's corps into retreat to the Plancenoit area, driving Lobau past the rear of the Armee Du Nord's right flank and directly threatening its only line of retreat. Hiller's 16th Brigade also pushed forward with six battalions against Plancenoit.[32][191]

Napoleon had dispatched all eight battalions of the Young Guard to reinforce Lobau, who was now seriously pressed. The Young Guard counter-attacked and, after very hard fighting, secured Plancenoit, but were themselves counter-attacked and driven out.[192] Napoleon sent two battalions of the Middle/Old Guard into Plancenoit and after ferocious bayonet fighting—they did not deign to fire their muskets—this force recaptured the village.[192]

Zieten's flank march

Throughout the late afternoon, the Prussian I Corps (Zieten's) had been arriving in greater strength in the area just north of La Haie. General Müffling, the Prussian liaison to Wellington, rode to meet Zieten.[193]

Zieten had by this time brought up the Prussian 1st Brigade (Steinmetz's), but had become concerned at the sight of stragglers and casualties from the Nassau units on Wellington's left and from the Prussian 15th Brigade (Laurens'). These troops appeared to be withdrawing and Zieten, fearing that his own troops would be caught up in a general retreat, was starting to move away from Wellington's flank and towards the Prussian main body near Plancenoit. Zieten had also received a direct order from Blücher to support Bülow, which Zieten obeyed, starting to march to Bülow's aid.[193]

Müffling saw this movement away and persuaded Zieten to support Wellington's left flank.[193] Müffling warned Zieten that "The battle is lost if the corps does not keep on the move and immediately support the English army."[194] Zieten resumed his march to support Wellington directly, and the arrival of his troops allowed Wellington to reinforce his crumbling centre by moving cavalry from his left.[193]

The French were expecting Grouchy to march to their support from Wavre, and when Prussian I Corps (Zieten's) appeared at Waterloo instead of Grouchy, "the shock of disillusionment shattered French morale" and "the sight of Zieten's arrival caused turmoil to rage in Napoleon's army".[195] I Corps proceeded to attack the French troops before Papelotte and by 19:30 the French position was bent into a rough horseshoe shape. The ends of the line were now based on Hougoumont on the left, Plancenoit on the right, and the centre on La Haie.[196]

Durutte had taken the positions of La Haie and Papelotte in a series of attacks,[196] but now retreated behind Smohain without opposing the Prussian 24th Regiment (Laurens') as it retook both. The 24th advanced against the new French position, was repulsed, and returned to the attack supported by Silesian Schützen (riflemen) and the F/1st Landwehr.[197] The French initially fell back before the renewed assault, but now began seriously to contest ground, attempting to regain Smohain and hold on to the ridgeline and the last few houses of Papelotte.[197]

The Prussian 24th Regiment linked up with a Highlander battalion on its far right and along with the 13th Landwehr Regiment and cavalry support threw the French out of these positions. Further attacks by the 13th Landwehr and the 15th Brigade drove the French from Frichermont.[198] Durutte's division, finding itself about to be charged by massed squadrons of Zieten's I Corps cavalry reserve, retreated from the battlefield. The rest of d'Erlon's I Corps also broke and fled in panic, while to the west the French Middle Guard were assaulting Wellington's centre.[199][200] The Prussian I Corps then advanced towards the Brussels road, the only line of retreat available to the French.

Attack of the Imperial Guard

Meanwhile, with Wellington's centre exposed by the fall of La Haye Sainte and the Plancenoit front temporarily stabilised, Napoleon committed his last reserve, the hitherto-undefeated Imperial Guard infantry. This attack, mounted at around 19:30, was intended to break through Wellington's centre and roll up his line away from the Prussians. Although it is one of the most celebrated passages of arms in military history, it had been unclear which units actually participated. It appears that it was mounted by five battalions of the Middle Guard,[aj] and not by the grenadiers or chasseurs of the Old Guard. Three Old Guard battalions did move forward and formed the attack's second line, though they remained in reserve and did not directly assault the Anglo-allied line.[201][ak]

... I saw four regiments of the middle guard, conducted by the Emperor, arriving. With these troops, he wished to renew the attack, and penetrate the centre of the enemy. He ordered me to lead them on; generals, officers and soldiers all displayed the greatest intrepidity; but this body of troops was too weak to resist, for a long time, the forces opposed to it by the enemy, and it was soon necessary to renounce the hope which this attack had, for a few moments, inspired.

— Marshal M. Ney.[202]

Napoleon himself oversaw the initial deployment of the Middle and Old Guard. The Middle Guard formed in battalion squares, each about 550 men strong, with the 1st/3rd Grenadiers, led by Generals Friant and Poret de Morvan, on the right along the road, to their left and rear was General Harlet leading the square of the 4th Grenadiers, then the 1st/3rd Chasseurs under General Michel, next the 2nd/3rd Chasseurs and finally the large single square of two battalions of 800 soldiers of the 4th Chasseurs led by General Henrion. Two batteries of Imperial Guard Horse Artillery accompanied them with sections of two guns between the squares. Each square was led by a general and Marshal Ney, mounted on his 5th horse of the day, led the advance.[203] Behind them, in reserve, were the three battalions of the Old Guard, right to left 1st/2nd Grenadiers, 2nd/2nd Chasseurs and 1st/2nd Chasseurs. Napoleon left Ney to conduct the assault; however, Ney led the Middle Guard on an oblique towards the Anglo-allied centre right instead of attacking straight up the centre. Napoleon sent Ney's senior ADC Colonel Crabbé to order Ney to adjust, but Crabbé was unable to get there in time.[citation needed]

Other troops rallied to support the advance of the Guard. On the left infantry from Reille's corps that was not engaged with Hougoumont and cavalry advanced. On the right all the now rallied elements of D'Érlon's corps once again ascended the ridge and engaged the Anglo-allied line. French artillery also moved forward in support; Duchand's battery, in particular, inflicting losses on Colin Halkett's brigade.[204] Halkett's front line, consisting of the 30th Foot and 73rd, traded fire with the 1st/3rd and 4th Grenadiers but they were driven back in confusion into the 33rd and 69th regiments, Halket was shot in the face and seriously wounded and the whole brigade having been ordered to pull back, retreated in a mob. Other Anglo-allied troops began to give way as well. A counterattack by the Nassauers and the remains of Kielmansegge's brigade from the Anglo-allied second line, led by the Prince of Orange, was also thrown back and the Prince of Orange was seriously wounded. The survivors of Halkett's brigade were reformed, and engaged the French in a firefight.[205][206]

I saw the Garde Impériale advancing while the English troops were leaving the plateau en masse and moving in the direction of Waterloo; the battle seemed lost...

The Dutch divisional commander Chassé, on his own initiative, decided at this critical moment to advance with his relatively fresh Dutch division.[208][207] Chassé first ordered his artillery forward;[207] led by a battery of Dutch horse-artillery commanded by Captain Krahmer de Bichin. The battery opened a destructive fire into the 1st/3rd Grenadiers' flank.[209] This still did not stop the Guard's advance, so Chassé, who was affectionately called "Generaal Bajonet" by his soldiers, ordered his first brigade, commanded by Colonel Hendrik Detmers, to charge the outnumbered French with the bayonet.[210][211] As the Guard wavered Chassé galloped among his men and found Captain De Haan with a few soldiers of the 19th Militia, whom he ordered into a flank attack. According to Chassé:

[De Haan] jumped over the hedge, reformed the line of about fifty men and the murderous fire he inflicted caused death and confusion among the enemy's lines. He took advantage of their confusion and advanced with the bayonet against them. I had the unspeakable joy to witness 300 Cuirassiers run away from 50 Dutchmen.[207]

The French grenadiers then faltered and broke. The 4th Grenadiers, seeing their comrades retreat and having suffered heavy casualties themselves, now wheeled right about and retired.[212]

To the left of the 4th Grenadiers were the two squares of the 1st/ and 2nd/3rd Chasseurs who angled further to the west and had suffered more from artillery fire than the grenadiers. But as their advance mounted the ridge they found it apparently abandoned and covered with dead. Suddenly 1,500 British Foot Guards under Peregrine Maitland, who had been lying down to protect themselves from the French artillery, rose and devastated them with point-blank volleys. The chasseurs deployed to answer the fire, but some 300 fell from the first volley, including Colonel Mallet and General Michel, and both battalion commanders.[213] A bayonet charge by the Foot Guards then broke the leaderless squares, which fell back onto the following column. The 4th Chasseurs battalion, 800 strong, now came up onto the exposed battalions of British Foot Guards, who lost all cohesion and dashed back up the slope as a disorganized crowd with the chasseurs in pursuit. At the crest the chasseurs came upon the battery that had caused severe casualties on the 1st and 2nd/3rd Chasseurs. They opened fire and swept away the gunners. The left flank of their square now came under fire from a heavy formation of British skirmishers, which the chasseurs drove back. But the skirmishers were replaced by the 52nd Light Infantry (2nd Division), led by John Colborne, which wheeled in line onto the chasseurs' flank and poured a devastating fire into them. The chasseurs returned a very sharp fire which killed or wounded some 150 men of the 52nd.[214] The 52nd then charged,[215][216] and under this onslaught, the chasseurs broke.[216]

The last of the Guard retreated headlong. A ripple of panic passed through the French lines as the astounding news spread: "La Garde recule. Sauve qui peut!" ("The Guard is retreating. Every man for himself!") Wellington now stood up in Copenhagen's stirrups and waved his hat in the air to signal a general advance. His army rushed forward from the lines and threw themselves upon the retreating French.[217][218]

The surviving Imperial Guard rallied on their three reserve battalions (some sources say four) just south of La Haye Sainte for a last stand. A charge from Adam's Brigade and the Hanoverian Landwehr Osnabrück Battalion, plus Vivian's and Vandeleur's relatively fresh cavalry brigades to their right, threw them into confusion. Those left in semi-cohesive units retreated towards La Belle Alliance. It was during this retreat that some of the Guards were invited to surrender, eliciting the famous, if apocryphal,[al] retort "La Garde meurt, elle ne se rend pas!" ("The Guard dies, it does not surrender!").[219][am]

Prussian capture of Plancenoit

At about the same time, the Prussian 5th, 14th, and 16th Brigades were starting to push through Plancenoit, in the third assault of the day. The church was by now on fire, while its graveyard—the French centre of resistance—had corpses strewn about "as if by a whirlwind". Five Guard battalions were deployed in support of the Young Guard, virtually all of which was now committed to the defence, along with remnants of Lobau's corps. The key to the Plancenoit position proved to be the Chantelet woods to the south. Pirch's II Corps had arrived with two brigades and reinforced the attack of IV Corps, advancing through the woods.[220]

The 25th Regiment's musketeer battalions threw the 1/2e Grenadiers (Old Guard) out of the Chantelet woods, outflanking Plancenoit and forcing a retreat. The Old Guard retreated in good order until they met the mass of troops retreating in panic, and became part of that rout. The Prussian IV Corps advanced beyond Plancenoit to find masses of French retreating in disorder from British pursuit. The Prussians were unable to fire for fear of hitting Wellington's units. This was the fifth and final time that Plancenoit changed hands.[220]

French forces not retreating with the Guard were surrounded in their positions and eliminated, neither side asking for nor offering quarter. The French Young Guard Division reported 96 per cent casualties, and two-thirds of Lobau's Corps ceased to exist.[citation needed]

Despite their great courage and stamina, the French Guards fighting in the village began to show signs of wavering. The church was already on fire with columns of red flame coming out of the windows, aisles and doors. In the village itself—still the scene of bitter house-to-house fighting—everything was burning, adding to the confusion. However, once Major von Witzleben's manoeuvre was accomplished and the French Guards saw their flank and rear threatened, they began to withdraw. The Guard Chasseurs under General Pelet formed the rearguard. The remnants of the Guard left in a great rush, leaving large masses of artillery, equipment and ammunition wagons in the wake of their retreat. The evacuation of Plancenoit led to the loss of the position that was to be used to cover the withdrawal of the French Army to Charleroi. The Guard fell back from Plancenoit in the direction of Maison du Roi and Caillou. Unlike other parts of the battlefield, there were no cries of "Sauve qui peut!" here. Instead, the cry "Sauvons nos aigles!" ("Let's save our eagles!") could be heard.

— Official History of the 25th Regiment, 4 Corps[220]

French disintegration

The French right, left, and centre had all now failed.[220] The last cohesive French force consisted of two battalions of the Old Guard stationed around La Belle Alliance; they had been so placed to act as a final reserve and to protect Napoleon in the event of a French retreat. He hoped to rally the French army behind them,[221] but as retreat turned into rout, they too were forced to withdraw, one on either side of La Belle Alliance, in square as protection against Coalition cavalry. Until persuaded that the battle was lost and he should leave, Napoleon commanded the square to the left of the inn.[93][222] Adam's Brigade charged and forced back this square,[216][223] while the Prussians engaged the other.

As dusk fell, both squares withdrew in relatively good order, but the French artillery and everything else fell into the hands of the Prussian and Anglo-allied armies. The retreating Guards were surrounded by thousands of fleeing, broken French troops. Coalition cavalry harried the fugitives until about 23:00, with Gneisenau pursuing them as far as Genappe before ordering a halt. There, Napoleon's abandoned carriage was captured, still containing an annotated copy of Machiavelli's The Prince, and diamonds left behind in the rush to escape. These diamonds became part of King Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia's crown jewels; one Major Keller of the F/15th received the Pour le Mérite with oak leaves for the feat.[224] By this time 78 guns and 2,000 prisoners had also been taken, including more generals.[225]

There remained to us still four squares of the Old Guard to protect the retreat. These brave grenadiers, the choice of the army, forced successively to retire, yielded ground foot by foot, till, overwhelmed by numbers, they were almost entirely annihilated. From that moment, a retrograde movement was declared, and the army formed nothing but a confused mass. There was not, however, a total rout, nor the cry of sauve qui peut, as has been calumniously stated in the bulletin.

— Marshal M. Ney.[226]