Vision for Space Exploration

The Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) was a plan for space exploration announced on January 14, 2004 by President George W. Bush. It was conceived as a response to the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, the state of human spaceflight at NASA, and as a way to regain public enthusiasm for space exploration.[1]

The policy outlined by the "Vision for Space Exploration" was replaced first by President Barack Obama's space policy in April 2010, then by President Donald Trump's "National Space Strategy" space policy in March 2018, and finally by President Joe Biden's preliminary space policy proposals in spring 2021.

Outline

[edit]The Vision for Space Exploration sought to implement a sustained and affordable human and robotic program to explore the Solar System and beyond; extend human presence across the Solar System, starting with a human return to the Moon by the year 2020, in preparation for human exploration of Mars and other destinations; develop the innovative technologies, knowledge, and infrastructures both to explore and to support decisions about the destinations for human exploration; and to promote international and commercial participation in exploration to further U.S. scientific, security, and economic interests.[2]

In pursuit of these goals, the Vision called for the space program to complete the International Space Station by 2010; retire the Space Shuttle by 2010; develop a new Crew Exploration Vehicle (later renamed Orion) by 2008, and conduct its first human spaceflight mission by 2014; explore the Moon with robotic spacecraft missions by 2008 and crewed missions by 2020, and use lunar exploration to develop and test new approaches and technologies useful for supporting sustained exploration of Mars and beyond; explore Mars and other destinations with robotic and crewed missions; pursue commercial transportation to support the International Space Station and missions beyond low Earth orbit.[2][3]

Outlining some of the advantages, U.S. President George W. Bush addressed the following:[3]

Establishing an extended human presence on the moon could vastly reduce the costs of further space exploration, making possible ever more ambitious missions. Lifting heavy spacecraft and fuel out of the Earth's gravity is expensive. Spacecraft assembled and provisioned on the moon could escape its far lower gravity using far less energy, and thus, far less cost. Also, the moon is home to abundant resources. Its soil contains raw materials that might be harvested and processed into rocket fuel or breathable air. We can use our time on the moon to develop and test new approaches and technologies and systems that will allow us to function in other, more challenging environments.

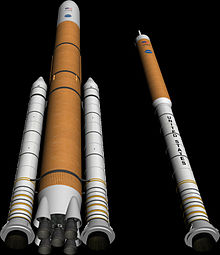

One of the stated goals for the Constellation program is to gain significant experience in operating away from Earth's environment,[4] as the White House contended, to embody a "sustainable course of long-term exploration."[5] The Ares boosters are a cost-effective approach[6] – entailing the Ares V's enormous, unprecedented cargo-carrying capacity[7] – transporting future space exploration resources to the Moon's[6] weaker gravity field.[8] While simultaneously serving as a proving ground for a wide range of space operations and processes, the Moon may serve as a cost-effective construction, launching and fueling site for future space exploration missions.[9] For example, future Ares V missions could cost-effectively[6] deliver raw materials for future spacecraft and missions to a Moon-based[6] space dock positioned as a counterweight to a Moon-based space elevator.[10]

NASA has also outlined plans for human missions to the far side of the Moon.[11] All of the Apollo missions have landed on the near side. Unique products may be producible in the nearly extreme vacuum of the lunar surface, and the Moon's remoteness is the ultimate isolation for biologically hazardous experiments. The Moon would also become a proving ground toward the development of In-Situ Resource Utilization, or "living off the land" (i.e., self-sufficiency) for permanent human outposts.

In a position paper issued by the National Space Society (NSS), a return to the Moon should be considered a high priority space program, to begin development of the knowledge and identification of the industries unique to the Moon. The NSS believes that the Moon may be a repository of the history and possible future of Earth, and that the six Apollo landings only scratched the surface of that "treasure". According to NSS, the Moon's far side, permanently shielded from the noisy Earth, is an ideal site for future radio astronomy (for example, signals in the 1–10 MHz range cannot be detected on Earth because of ionosphere interference[12]).

When the Vision was announced in January 2004, the U.S. Congress and the scientific community gave it a mix of positive and negative reviews. For example, U.S. Representative Dave Weldon (Republican–Florida) said, "I think this is the best thing that has happened to the space program in decades." Though physicist and outspoken crewed spaceflight opponent Robert L. Park stated that robotic spacecraft "are doing so well it's going to be hard to justify sending a human,"[5] the vision announced by the President states that "robotic missions will serve as trailblazers—the advanced guard to the unknown."[3] Others, such as the Mars Society, have argued that it makes more sense to avoid going back to the Moon and instead focus on going to Mars first.[13]

Throughout much of 2004, it was unclear whether the U.S. Congress would be willing to approve and fund the Vision for Space Exploration. However, in November 2004, Congress passed a spending bill which gave NASA the $16.2 billion that President Bush had sought to kick-start the Vision. According to then-NASA chief Sean O'Keefe, that spending bill "was as strong an endorsement of the space exploration vision, as any of us could have imagined."[14] In 2005, Congress passed S.1281, the NASA Authorization Act of 2005, which explicitly endorsed the Vision.[15]

Former NASA Administrator Michael Griffin is a supporter of the Vision, but modified it somewhat, saying that he wants to reduce the four-year gap between the retirement of the Space Shuttle and the first crewed mission of the Crew Exploration Vehicle.[16]

Lunar Architecture

[edit]NASA's "Lunar Architecture" forms a key part of its Global Exploration Strategy, also known as the Vision for Space Exploration. The first part of the Lunar Architecture is the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which launched in June 2009 on board an Atlas V. The preliminary design review was completed in February 2006 and the critical design review was completed in November 2006. An important function of the orbiter will be to look for further evidence that the increased concentrations of hydrogen discovered at the Moon's poles is in the form of lunar ice. After this the lunar flights will make use of the new Ares I and Ares V rockets.[17]

Critical perspectives

[edit]

In December 2003, Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin voiced criticism for NASA's vision and objectives, stating that the goal of sending astronauts back to the Moon was "more like reaching for past glory than striving for new triumphs".[18]

In February 2009, the Aerospace Technology Working Group released an in-depth report asserting that the Vision had several fundamental problems with regard to politics, financing, and general space policy issues and that the initiative should be rectified or replaced.[19]

Another concern noted is that funding for VSE could instead be harnessed to advance science and technology, such as in aeronautics, commercial spacecraft and launch vehicle technology, environmental monitoring, and biomedical sciences.[20] However, VSE itself is poised to propel a host of beneficial Moon science activities, including lunar telescopes, selenological studies and solar energy beams.

With or without VSE, human spaceflight will be made sustainable. However, without VSE, more funds could be directed toward reducing human spaceflight costs sufficiently for the betterment of low Earth orbit research, business, and tourism.[20] Alternatively, VSE could afford advances in other scientific research (astronomy, selenology), in-situ lunar business industries, and lunar-space tourism.

The VSE budget required termination the Space Shuttle by 2010 and of any US role in the International Space Station by 2017. This would have required, even in the most optimistic plans, a period of years without human spaceflight capability from the US. Termination of the Space Shuttle program, without any planned alternatives, in 2011 ended virtually all US capability for reusable launch vehicles. This severely limited any future of low Earth orbit or deep space exploration. Ultimately, the lack of proper funding caused the VSE to fall short of its original goals, leaving many projects behind schedule as President George W. Bush's term in office ended.

Keith Cowan wrote in 2014, "The damage done to America and the rest of the world by unsustainable deficits is real, and any lack of zeal in facing this problem would be a mistake. In that context, this would be a good time for Congress to look again at Bush's plans for NASA to re-establish a human presence in deep space. The outgoing Republican Congress gave its Republican president too much benefit of the doubt on this undertaking. The new Congress must, at the very least, articulate more convincing reasons than have yet been heard for such a colossal expenditure."[21]

"A large portion of the scientific community" concurs that NASA is not "expanding our scientific understanding of the universe" in "the most effective or cost-efficient way."[Tumlinson 1] Proponents for VSE argue that a permanent settlement on the moon would drastically reduce costs for further space exploration missions. President George W. Bush voiced this sentiment when the vision was first announced (see quote above), and the United States Senate has re-entered testimony[Tumlinson 1] by Space Frontier Foundation founder Rick Tumlinson offered previously to the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation advocating this particular perspective.[Tumlinson 1] The reason that the National Space Society regards a return to the Moon as a high space program priority is to begin development of the knowledge and identification of the industries unique to the Moon, because "such industries can provide economic leverage and support for NASA activities, saving the government millions."[Tumlinson 2]

As Tumlinson additionally notes, the goal is to "open space ... to human settlement ... to create ways to harvest the resources ... not only saving this precious planet, but also ... assuring our survival."[Tumlinson 3] Regarding "the Moon, NASA should support early exploration now. ... "[Tumlinson 4]

Mars vision

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2021) |

-

Concept art by NASA of two people in suits on Mars setting up weather equipment.[22]

-

NASA concept of Mars-crew analyzing a sample (2004).[23]

-

An artist's conception, from NASA, of an astronaut planting a US flag on Mars.

Interplanetary human transport

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2021) |

See also

[edit]- Artemis program

- Aurora programme

- Crew Exploration Vehicle

- Crew Space Transportation System

- Decadal Planning Team

- DIRECT

- Exploration Systems Architecture Study

- Google Lunar X Prize

- Human Lunar Return study

- Human spaceflight

- Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

- Colonization of the Moon

- Constellation program

- Colonization of Mars

- Space advocacy

- Space exploration

- Space Exploration Initiative

References

[edit]- ^ "President Bush Announces New Vision for Space Exploration Program". NASA. 20 January 2004. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ a b "The Vision for Space Exploration" (PDF). NASA. February 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2004. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ a b c "President Bush Announces New Vision for Space Exploration Program". NASA. January 14, 2004. Retrieved June 17, 2009.

- ^ Connolly, John F. (October 2006). "Constellation Program Overview" (PDF). Constellation Program Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ a b "FAQ: Bush's New Space Vision". space.com. 19 September 2005. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Ares I Crew Launch Vehicle". NASA. April 29, 2009. Archived from the original on November 5, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- ^ Creech, Steve and Phil Sumrall. "Ares V: Refining a New Heavy Lift Capability". NASA.

- ^ Williams, Dr. David R. (February 2, 2006). "Moon Fact Sheet". NASA (National Space Science Data Center). Retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ^ Van Susante, P. J.; Imhof, B.; S. Mohanty; H.J. Rombaut; J. Volp (December 1, 2002). Highlights on Lunar Base Designs (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2010. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ Pearson, Jerome; Eugene Levin; John Oldson & Harry Wykes (2005). "Lunar Space Elevators for Cislunar Space Development Phase I Final Technical Report" (PDF).

- ^ Leake, Jonathan (March 19, 2006). "Nasa to put man on far side of moon". Times Online. Times Newspapers. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ LIFE on Moon, Archived 2010-03-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "The Mars Society Frequently Asked Questions". marssociety.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- ^ "Congress Grants $16.2 Billion Budget for NASA". space.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2005. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- ^ "NASA Authorization Act" (PDF). gpo.gov. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- ^ "A Message From Administrator Michael Griffin". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on September 13, 2005. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- ^ "NASA Unveils Global Exploration Strategy and Lunar Architecture". NASA. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-08-23.

- ^ Aldrin, Buzz (December 5, 2003). "Fly Me To L1". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2009. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ Hsu, Feng; Cox, Ken (February 20, 2009). "Sustainable Space Exploration and Space Development – A Unified Strategic Vision". Aerospace Technology Working Group. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ a b Woodard, Daniel (2009). "Practical Benefits for America" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 28, 2009. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (16 November 2006). "Nature of Funding the VSE". NASA Watch. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- ^ "Photo-jsc2004e18853". spaceflight.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 17 November 2004. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Photo-jsc2004e18859". spaceflight.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 18 November 2004. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- Tumlinson, Rick. Testimony to United States Senate Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Ares Web Site

- Constellation NASA Web Site

- NASA Authorization Act of 2005

- NASA: Exploration Systems

- NASA: The Vision for Space Exploration

- National Space Society

- Orion Web Site

- President's Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy

- "The Vision for Space Exploration" Original Document, February 2004

- Vision for Space Exploration Gallery

![Concept art by NASA of two people in suits on Mars setting up weather equipment.[22]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8f/Manned_mission_to_Mars_%28artist%27s_concept%29.jpg/240px-Manned_mission_to_Mars_%28artist%27s_concept%29.jpg)

![NASA concept of Mars-crew analyzing a sample (2004).[23]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Jsc2004e18859.jpg/240px-Jsc2004e18859.jpg)