Boggart

The Bannister Hall Doll, a boggart said to have haunted Bannister Hall in Higher Walton, Preston, in two of its forms | |

| Grouping | Folklore creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Household spirit, or ogre attached to a particular location |

| Similar entities | See here |

| Folklore | English folklore |

| Other name(s) | Boggard (in Yorkshire) |

| Country | England |

| Region | Parts of Northern England, particularly the North West |

| Habitat | Both within homes and outside in the countryside. |

A boggart is a supernatural being from English folklore. The dialectologist Elizabeth Wright described the boggart as 'a generic name for an apparition';[1] folklorist Simon Young defines it as 'any ambivalent or evil solitary supernatural spirit'.[2] Halifax folklorist Kai Roberts states that boggart ‘might have been used to refer to anything from a hilltop hobgoblin to a household faerie, from a headless apparition to a proto-typical poltergeist’.[3] As these wide definitions suggest boggarts are to be found both in and out of doors, as a household spirit, or a malevolent spirit defined by local geography, a genius loci inhabiting topographical features. The 1867 book Lancashire Folklore by Harland and Wilkinson, makes a distinction between "House boggarts" and other types.[4] Typical descriptions show boggarts to be malevolent. It is said that the boggart crawls into people's beds at night and puts a clammy hand on their faces. Sometimes he strips the bedsheets off them.[5] The household boggart may follow a family wherever they flee. One Lancashire source reports the belief that a boggart should never be named: if the boggart was given a name, it could neither be reasoned with nor persuaded, but would become uncontrollable and destructive (see True name).[6]

Etymology

[edit]Boggart is written in many different forms: "boggard" (particularly in Yorkshire), "baggard", "bogerd", "boggat", "bogard", "boggerd", "boggert", "bugart", "buggard", and "buggart".[7] Boggart is ultimately the typical Lancashire dialect form. These forms all point to an origin with the Middle English word bugge (a spirit or monster) with an aggrandizing suffix making boggart, a great big bugge. This also makes boggart a close linguistic cousin of "bogle" (or boggle, a Scots variant), 'bugaboo', "bugbear", "bug", "bogeyman" and "bogie", all of which also derive from bugge. Bugge may, in turn, be related to other British and Irish supernatural terms like "bucca", "pwca", "Puck" and "pooka", but this is uncertain.[8]

Dialect

[edit]In north-western dialects the word 'boggart' was used in a number of sentences. In Lancashire, a skittish or runaway horse was said to have "took boggarts"—that is, been frightened by a, usually invisible, boggart.[9] 'Boggart muck' seems to have been a word for owl pellets in much of North West England.[10]

Appearance

[edit]The recorded folklore of boggarts is remarkably varied as to their appearance and size. Many are described as relatively human-like in form, though usually uncouth, very ugly and often with bestial attributes. T. Sternberg's 1851 book Dialect and Folk-lore of Northhamptonshire describes a certain boggart as "a squat hairy man, strong as a six year old horse, and with arms almost as long as tacklepoles".[11]

Other accounts describe boggarts as having more completely beast-like forms. The "Boggart of Longar Hede" from Yorkshire was said to be a fearsome creature the size of a calf, with long shaggy hair and eyes like saucers. It trailed a long chain after itself, which made a noise like the baying of hounds.[12] The "Boggart of Hackensall Hall" in Lancashire had the appearance of a huge horse.[13]

At least one Lancashire boggart was said to sometimes take the forms of various animals, or indeed more fearful creatures.[14] The boggarts of Lancashire were said to have a leader, or master, called 'Owd Hob', who had the form of a satyr or archetypical devil: horns, cloven hooves and a tail.[15]

The name of at least one Lancashire boggart was recorded, "Nut-Nan", who flitted with a shrill scream among hazel bushes in Moston near Manchester.[16] In Yorkshire, boggarts also inhabit outdoor locations, one is said to haunt Cave Ha, a limestone cavern at Giggleswick near Settle.[17]

- Depictions of various Boggarts based on 19th Century sources

-

The Boggart of Fair Becca, as described in "Juvenile tales for boys and girls", William Milner, 1849, shrieking at a courting couple. Art by Jantiff Illustration

-

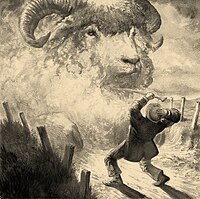

Sheep Boggart encountered near Carnforth - "The supposed sheep aroused itself and as if with indignity at the insult, swelled out as the man affirms, into the size of a house". Art by Jantiff Illustration

-

The Copp Boggart, in one of its forms - "A terrific dog with a white neck and a tail similar to a sheaf of corn curled up all over its shoulders". Art by Rhi Wynter

Grizlehurst boggart (Lancashire)

[edit]A piece of folklore concerning a Lancashire boggart was first published in 1861; the author, Edwin Waugh, had a conversation with an elderly couple one evening about their local boggart. They maintained that the boggart was buried at a nearby bend in the road under an ash tree, along with a cockerel with a stake driven through it. Despite being buried, the boggart was still able to create trouble. A farmer's wife, the old couple claimed, just two weeks earlier had heard doors banging in her farmhouse at night, then loud laughter; she looked out to see three candles casting blue light and a creature with red burning eyes leaping about. The following morning many marks of cloven hooves were seen outside the house. The couple claimed that the boggart had unhitched their own horse and overturned their cart on occasion. "Never name it [the boggart]" the old woman repeated, and her husband stated that he would never dig near its grave.[18]

The Farmer and the Boggart

[edit]In one old tale, said to originate from the village of Mumby in the Lincolnshire countryside, the boggart is described as being rather squat, hairy, and smelly. In the story, a farmer offers a deal to a boggart inhabiting his land; the boggart may choose either the part of the crop that grows above the ground or the part below it. When the boggart chooses the part below the ground, the farmer plants barley; at harvest time, the boggart is left with only stubble. The boggart then demands the part above ground instead, so the farmer plants potatoes. Once again left with nothing to show for his efforts, the enraged boggart leaves the area.[19]

An alternative telling includes a third episode where the farmer and the boggart are to harvest the crop (wheat) from either side of the field, each getting what he harvests. However the farmer plants iron rods in the boggart's half before the reaping, blunting his scythe, and allowing the farmer to harvest almost the entire field.[20]

This story is identical to the European fable The Farmer and the Devil, cited in many seventeenth-century French works. (See Bonne Continuation, Nina M. Furry et Hannelore Jarausch).

Distribution and place names

[edit]

The word 'boggart' is especially associated with Lancashire. But distribution maps show that "Boggartdom" (the area in which stories of boggarts are found) extended to northern Cheshire, much of Derbyshire, northern Lincolnshire, the old West Riding of Yorkshire, parts of the North Riding, the fringes of Westmorland, and perhaps Nottinghamshire, and possibly, at one time, as far north as Cleveland and as far south as Skegness.[21] In other parts of northern England and the Scottish Lowlands, alternative 'bog' words were used such as 'bogie' and 'bogle'.

A variety of geographic locations and architectural landmarks have been named for the boggart. Most famously there is a large municipal park called Boggart Hole Clough, which is bordered by Moston and Blackley in Manchester. "Clough" is a northern dialect word for a steep-sided, wooded valley; a large part of Boggart Hole Clough is made up of these valleys and is said to be inhabited by boggarts.[22] The clough is the setting for many boggart stories, including one of how a local farmer, George Cheetham, and his family were forced to leave their home due to the torment inflicted by a boggart. However, as they were taking their possessions away in a cart, the voice of the boggart was heard issuing from a milk-churn on the cart. Unable to escape the boggart, they returned to their farm.[23]

There is a Boggart Stones on Saddleworth Moor where the Moors Murderers, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, buried the bodies of Pauline Reade and Lesley Ann Downey, children they had abducted, in 1963 and 1964. The children's bodies were buried just below the location, and in sight of, Boggart Stones (OS Map 1864). There is a Boggart Bridge in Burnley, Lancashire. Tradition says that whoever crosses the bridge must give a living thing to the boggart or forfeit his or her soul. Boggarts Roaring Holes are a group of potholes on the moors of Newby Moss near Clapham in the Yorkshire Dales. Legend has it that these potholes are the dwelling place of grotesque flesh-eating boggarts whose angry growls have allegedly been heard reverberating from the depths of the dark caverns beneath (hence the name). In the Seacroft area of Leeds in West Yorkshire there is a council estate named Boggart Hill; Boggart Hill Drive, Boggart Hill Gardens and Boggart Hill were all given the name of the estate area. Boggard Lane, between the villages of Oughtibridge and Worrall in South Yorkshire, is generally believed to derive from the term "boggart". There is also a Boggart Lane at Skelmanthorpe.

On Puck, a moon of Uranus, there is a crater named Bogle, in deference to the system of nomenclature on this satellite, whose features are all named after various mischievous spirits.

The Boggart Census

[edit]In 2019 folklorist Simon Young launched a survey to test modern understandings of the word 'boggart' in England and particularly Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire and Yorkshire. Young collected 1,100 accounts, including about 400 negatives ('from the middle-aged and the elderly saying that they had never heard of boggarts while growing up').[24] The census was released freely online by University of Exeter Press as an open access pdf.[25]

In popular culture

[edit]

Fiction

[edit]Boggarts feature prominently in a number of popular fantasy novels, in various incarnations.[26] These include the boggart in Susan Cooper's The Boggart and The Boggart and the Monster, the boggart in the Septimus Heap series, the boggarts in Joseph Delaney's Spook's series, and the boggart in William Mayne's Earthfasts, and Tasha Tudor's Corgi-related picture books.

A boggart appears in Peter S. Beagle's novel Tamsin. He is described as a humanoid creature about a meter high who resents humans moving into his house and torments them with pranks and thievery. It seems he can become invisible at first, but it is later determined that he can hide in narrow cracks such as those between cupboards and under bathtubs. As are many magical creatures in the book, the boggart is mortally afraid of cats.

The boggarts in J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter are shape-shifters whose true form is unknown, that change shape to resemble their beholder's worst fear (possibly inspired by the "clutterbumph" in Paul Gallico's Manxmouse). They are unlike most boggarts of British folklore, whose appearance is fixed. Their closest parallel for a boggart able to change shape at will is probably to be found in a reference to a Lancashire boggart in the book Lancashire Folklore of 1867.[14]

In some contemporary fantasy fiction and films such as The Spiderwick Chronicles[citation needed], Mark Del Franco's Convergent World books, and the fantasy writing of Juliana Horatio Ewing, boggarts are brownies who have been angered or become malevolent. This has been adopted into folklore studies but is not found in traditional sources.[27]

Film and television

[edit]In the 2014 fantasy film Seventh Son an enormous malevolent boggart attacks the protagonists while they are on their journey to find the antagonist character. Boggarts also appear in the film's original source material, The Spook's Apprentice. In the CITV children's show The Treacle People, boggarts are furry, gremlin-like creatures that originate from the Treacle Mines. They are mischievous, frequently playfighting and causing a mess. They serve as pets, friends and pests to the townspeople. They have the ability to walk up walls and other inclined surfaces due to their feet, which resemble plungers. Kamen Rider Wizard features a villain of the week based on the boggart.

Games

[edit]In the Magic: The Gathering card game's Lorwyn block, the native goblins of the plane are called boggarts. In role-playing games, the boggart appeared as the immature form of a will-o'-wisp with shape-shifting abilities in Dungeons & Dragons[28] as well as Necromancer Games.[29] A boggart appears in the game Home Safety Hotline [30]

Boggarts and bogs

[edit]The connection between the word boggart and 'bog' depends on folk etymology: there is no obvious association in many earlier sources between boggarts and the word 'bog'; though this is frequent in post-war accounts.[31] However, in Lincolnshire, the intimate connection of boggarts with marshland is attested in a 19th-century account. In this account the descriptive phrase 'swamp bogles' is also employed.[32] In 1882, the weekly journal All the Year Round, then edited by Charles Dickens Jr., describes a marsh-dwelling boggart, who milked farmers' cows at night.[33] In Lancashire, when a person got lost in a marsh and was never seen again, the people were sure that a boggart had caught the poor unfortunate and devoured him.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wright, Elizabeth Mary, Rustic Speech and Folk-lore (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1918), 192.

- ^ Young 2022, p. 7

- ^ Haunted Halifax and District (Stroud: History Press, 2014), 52.

- ^ Harland and Wilkinson, pp. 56, 58.

- ^ Harland and Wilkinson, p. 55

- ^ Waugh, pp. 18-19; cited in Hardwick, p. 132

- ^ Young, The Boggart, xiii.

- ^ Young, The Boggart, 28-29; Widdowson, 'The Bogeyman', 112.

- ^ Young, Boggart, 245

- ^ Young, Boggart, 234-235.

- ^ Saga Book, p, 37.

- ^ Cordner, p. 30

- ^ Harland and Wilkinson, p. 59

- ^ a b Harland and Wilkinson, p. 55.

- ^ a b Griffiths

- ^ Sayce, p. 76.

- ^ Hughes, pp. 386-387

- ^ Waugh, pp. 18-22

- ^ Saga Book, pp. 36-39

- ^ Adrian Gray (1900). Tales of Old Lincolnshire (reprinted 2001 ed.). Countryside Books. pp. 29–34. ISBN 978-1-85306-089-2.

- ^ Young, Boggart, 50-70.

- ^ Harland and Wilkinson, pp. 50-51.

- ^ Waugh, Edwin, (1869) Lancashire Sketches, John Heywood, Manchester. pp.183-185

- ^ Young, The Boggart, 21-24.

- ^ "The Boggart Sourcebook".

- ^ Young (2022), entire Chapter 8 - "The New Boggart"

- ^ Young, The Boggart, 203-207; https://writinginmargins.weebly.com/home/can-brownies-become-boggarts 'Can Brownies Become Boggarts'

- ^ Gygax, Gary. Monster Manual II (TSR, 1983)

- ^ Green, Scott; Peterson, Clark (2002). Tome of Horrors. Necromancer Games. pp. 26–27. ISBN 1-58846-112-2.

- ^ Wolens, Joshua. "Spooky '90s call centre sim Home Safety Hotline has wired up a direct line to my heart". PC Gamer. Future PLC. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Young, The Boggart, 31-3: 'Nor is there any sense that 'bog' influenced the popular view of the boggart in the nineteenth-century... There is some evidence... that twentieth-century views and illustrations of the boggart, depend on slime and boggy expanses.'

- ^ Balfour (1891), pp. 149-150, 154

- ^ All the Year Round: A Weekly Journal, Charles Dickens (Ed.) (1882) Vol. XXX, published at 26 Wellington St., Strand, London, p. 432

References

[edit]- Balfour, M.C. (1891) "Legends of the Cars", Folklore, 2:2, 145-170, DOI: 10.1080/0015587X.1891.9720054: https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.1891.9720054

- Briggs, K. M. (1957). "The English Fairies". Folklore. 68 (1): 270–287. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1957.9717577.

- Cordner, W.S. (1946). "The Cult of the Holy Well". Ulster Journal of Archaeology. Third Series. 9: 24–36.

- Griffiths, A. (1993). Lancashire Folklore. Leigh Local History Society. ISBN 9780905235134.

- Haase, D., ed. (2008). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales: G–P. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313334412.

- Hardwick, C. (1872) Traditions, Superstitions, and Folklore, (chiefly Lancashire and the North of England:) Their Affinity to Others in Widely distributed Localities; Their Eastern Origin and Mythical Significance, A. Ireland, London

- Harland, J; Wilkinson, T. T. (1857). Lancashire Folk-lore. Warne & Co.

- Harte, J. (1986). Cuckoo Pounds and Singing Barrows: The Folklore of Ancient Sites in Dorset. Dorset Natural History & Archaeological Society.

- Hughes, T.M. (1874). "Exploration of Cave Ha, Near Giggleswick, Settle, Yorkshire". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 3: 383–387. doi:10.2307/2840911. JSTOR 2840911.

- Saga-book of the Viking Club. Vol. 3. Viking Society for Northern Research. 1902.

- Sayce, R.V. (1956). "Folk-Lore, Folk-Life, Ethnology". Folklore. 67 (2): 66–83. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1956.9717527.

- Waugh, Edwin (1861). The Goblin's Grave. Edwin Slater.

- Widdowson, J. (1971). "The Bogeyman: Some Preliminary Observations on Frightening Figures". Folklore. 82 (2): 99–115. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1971.9716716.

- Young, Simon (2022). The Boggart: Folklore, History, Place-names and Dialect. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1905816903.

Further reading

[edit]- Young, Simon, editor. The Boggart Sourcebook: Texts and Memories for the Study of the British Supernatural. University of Exeter Press (doi:10.47788/QXUA4856). e-book

External links

[edit]- Bannister Hall (Preston) at fairyist.com