Vostok Island

Vostok Island | |

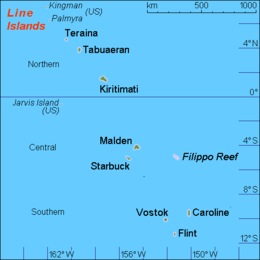

Map of the Line Islands | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | South Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 10°03′43″S 152°18′46″W / 10.06194°S 152.31278°W |

| Archipelago | Line Islands |

| Area | 0.24 km2 (0.093 sq mi) |

| Length | 0.7 km (0.43 mi) |

| Width | 0.6 km (0.37 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

Vostok Island is an uninhabited coral island in the central Pacific Ocean, part of the Line Islands belonging to Kiribati. Other names for the island include Anne Island, Bostock Island, Leavitts Island, Reaper Island, Wostock Island or Wostok Island. The island was first sighted in 1820 by the Russian explorer Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen, who named the island for his ship Vostok.[a]

Geography, flora and fauna

[edit]

Vostok covers a land area of 24 hectares (59 acres). Its nearest neighbors are Flint Island, 158 kilometres (98 miles) south-southeast; Caroline Atoll (renamed Millennium Island), 230 kilometres (140 miles) to the east; and Penrhyn, 621 kilometres (386 miles) to the west. It is 1.3 kilometres (0.8 miles) in length, and is triangular-shaped.[2]

Beaches on the island range between 25 and 30 metres (82 and 98 feet) wide, composed of coral sand and rubble. There is no lagoon or fresh water on the island, and no known freshwater lens. Vostok's major portion is covered with a pure stand of Pisonia trees rooted in moist peat soil one meter thick.[3] These trees, with heights of up to 30 metres (98 feet), grow so densely that no other plants can grow beneath them. The island's dense foliage looks dark from when viewed above. This gives the island the appearance of a mysterious black hole when seen on Google Earth which generated speculation in 2021, leading to many to believe that the island is being censored from public view. However this conclusion is easily refuted by other mapping services and publicly available images. [4]

The herbs Boerhavia repens and Sesuvium portulacastrum round out the known vegetation.[5] Although coconut seedlings were planted on Vostok in 1922 they failed to grow despite being successfully cultivated on the nearby islands of Caroline and Flint.[2]

Noteworthy fauna includes several species of seabirds, including the red-footed booby (Sula sula), great frigatebird (Fregata minor), lesser frigatebird (F. ariel), black noddy (Anous minutus), white tern (Gygis alba), masked booby (Sula dactylatra), brown booby (S. leucogaster) and brown noddy (Anous stolidus). The Polynesian rat and the copper-tailed skink (Emoia cyanura), together with coconut crabs and green turtles, completes the known land fauna.[3]

History

[edit]According to a 1966 article in Pacific Islands Monthly, there is no evidence of Polynesian settlement of Vostok Island prior to European discovery. Cook Islanders from Manihiki and Penrhyn atoll – the nearest inhabited islands to Vostok – interviewed in 1924 reported that they had no name for the island and were unaware of its existence.[6]

The island was first sighted in 1820 by the Russian explorer Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen, who named the island for his ship Vostok (the name means "East" in Russian).[1] Various whalers sighted the island over the following decades and believed it to be undiscovered, giving it the additional names of Stavers Island, Reaper Island, Leavitts Island and Anne Island.[6]

In 1841, the island was visited by USS Porpoise of the United States Exploring Expedition, which was unable to land due to heavy surf.[6] Vostok was claimed by the United States under the Guano Act of 1856, but was never mined for phosphate.[2] In 1874, guano entrepreneur John T. Arundel was granted licence to the island by the British Colonial Office. The coal barque Tokatea was wrecked on the island in 1879, with its crew making the first recorded landing and subsequently escaping to Tetiꞌaroa in the ship's boats. Arundel visited Vostok in 1883 to assess its potential and completed a survey for the Admiralty Office.[6]

Vostok formed part of the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, until becoming a part of newly independent Kiribati in 1979. American claims on the island were vacated in the Treaty of Tarawa in the same year.[7]

Vostok Island is designated as the Vostok Island Wildlife Sanctuary.[8][9] In 2014 the Kiribati government announced the establishment of a 12-nautical-mile fishing exclusion zone around each of the southern Line Islands (Caroline, Flint, Vostok, Malden, and Starbuck).[10]

Its isolated nature means it is rarely visited, save by the occasional scientist or yachter.[10] Passengers aboard the Golden Princess see it on the ship's route from French Polynesia to Hawaii. Landing is said to be difficult, and no harbor or anchorage exists.[6]

Photo gallery

[edit]-

Wind-shorn Pisonia trees on Vostok Island

-

Virgin forest of Pisonia trees covering Vostok Island

-

Western coastline of Vostok Island

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Armstrong, Terence (September 1971). "Bellingshausen and the discovery of Antarctica". Polar Record. 15 (99). Cambridge University Press: 887–889. Bibcode:1971PoRec..15..887A. doi:10.1017/S0032247400062112. S2CID 129664580.

- ^ a b c Resture, Jane. "Vostok Island, Line Islands". janeresture.com. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ a b Clapp, Roger B.; Sibley, Fred C. (16 February 1971). "The vascular flora and terrestrial vertebrates of Vostok Island, South-Central Pacific" (PDF). Atoll Research Bulletin. 144: 1–9. doi:10.5479/si.00775630.144.1. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ The mystery behind Google Maps' 'black hole' in the Pacific Ocean, BBC, 5 Nov 2021

- ^ Watkins, Doug; Batoromaio, Kiritian (2014). "Directory of Wetlands of Kiribati - 2014" (PDF). SPREP. p. 87. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Vostok Island's History Is Yet To Be Made". Pacific Islands Monthly. Vol. 37, no. 9. 1 September 1966. pp. 86–87. Retrieved 27 October 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ US Department of State Background Note

- ^ Edward R. Lovell, Taratau Kirata & Tooti Tekinaiti (September 2002). "Status report for Kiribati's coral reefs" (PDF). Centre IRD de Nouméa. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Paine, James R. (1991). IUCN Directory of Protected Areas in Oceania. World Conservation Union. ISBN 978-0-8248-1217-1.

- ^ a b Warne, Kennedy (September 2014). "A World Apart – The Southern Line Islands". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

External links

[edit]- National Geographic - Southern Line Islands Expedition, 2014 Archived 2017-08-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Article at Jane's Oceania Home Page - includes a sketch map

- Article at Looking For Nemo Expedition's site - includes photo and sketch map

- Oceandots - Vostok Island at the Wayback Machine (archived December 23, 2010) - satellite photograph