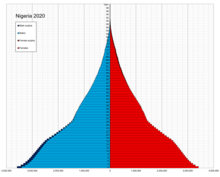

Population pyramid

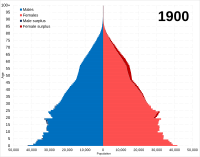

A population pyramid (age structure diagram) or "age-sex pyramid" is a graphical illustration of the distribution of a population (typically that of a country or region of the world) by age groups and sex; it typically takes the shape of a pyramid when the population is growing.[1] Males are usually shown on the left and females on the right, and they may be measured in absolute numbers or as a percentage of the total population. The pyramid can be used to visualize the age of a particular population.[2] It is also used in ecology to determine the overall age distribution of a population; an indication of the reproductive capabilities and likelihood of the continuation of a species. Number of people per unit area of land is called population density.

Structure

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2018) |

A population pyramid often contains continuous stacked-histogram bars, making it a horizontal bar diagram. The population size is shown on the x-axis (horizontal) while the age-groups are represented on the y-axis (vertical).[3] The size of each bar can be displayed either as a percentage of the total population or as a raw number. Males are conventionally shown on the left and females on the right. Population pyramids are often viewed as the most effective way to graphically depict the age and distribution of a population, partly because of the very clear image these pyramids provide.[4] A great deal of information about the population broken down by age and sex can be read from a population pyramid, and this can shed light on the extent of development and other aspects of the population.

The measures of central tendency (mean, median, and mode) should be considered when assessing a population pyramid. For example, the average age could be used to determine the type of population in a particular region. A population with an average age of 15 would be very young compared to one with an average age of 55. Population statistics are often mid-year numbers.

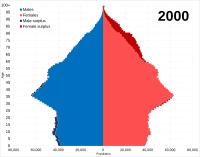

A series of population pyramids could give a clear picture of how a country transitions from high to low fertility rates. If the pyramid has a broad base, this indicates that a relatively high proportion of the population lies in the youngest age band, such as ages 0–14, which suggests that the fertility rate of the country is high and above replacement fertility level.[5] If a population is below replacement fertility level, the older population is declining with age, due to a combination of mortality and an increase in the number of births over time. There are usually more females than males in the older age ranges since, for a variety of reasons, women have a greater life expectancy.

The shape of the pyramid can also reveal the age-dependency ratio of a population. Populations with a high proportion of children and/or of elderly people have a higher dependency ratio. This ratio refers to how many old and young people are dependent on the working-age groups (often defined as ages 15–64). According to Weeks' Population: an Introduction to Concepts and Issues, population pyramids can be used to predict the future, known as a population forecast. Population momentum, when a population's birth rates continue to increase even after fertility rate has declined to replacement level, can even be predicted if a population has a low mortality rate since the population will continue to grow. This then brings up the term doubling time, which is used to predict when the population will double in size. Lastly, a population pyramid can even give insight into the economic status of a country from the age stratification since the distribution of supplies is not evenly distributed through a population.

Demographic transition

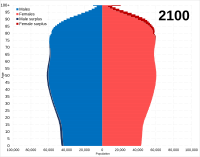

[edit]In the demographic transition model, the size and shape of population pyramids vary. In stage one of the demographic transition model, the pyramids have the most defined shape. They have the ideal big base and a skinny top. In stage two, the pyramid looks similar but starts to widen in the middle age groups. In stage three, the pyramids start to round out and look similar in shape to a tombstone. In stage four, there is a decrease in the younger age groups. This causes the base of the widened pyramid to narrow. Lastly, in stage five, the pyramid starts to take on the shape of a kite as the base continues to decrease. The shape of the population is dependent upon what the economy is like in the country. More developed countries can be found in stages three, four, and five, while the least developed countries have a population represented by the pyramids in stages one and two.

Types

[edit]

Each country will have a different population pyramid. However, population pyramids can be categorised into three types: stationary, expansive, or constrictive. These types have been identified by the fertility and mortality rates of a country.[6]

- "Stationary" pyramid or constant population pyramid

- A pyramid can be described as stationary if the percentages of population (age and sex) remain approximately constant over time.[7] In a stationary population, the numbers of births and death roughly balance one another.

- "Expansive" pyramid or Expanding population pyramid

- A population pyramid that is very wide at the younger ages, characteristic of countries with a high birth rate and perhaps low life expectancy therefore leading to high death rate.[6] The population is said to be fast-growing, and the size of each birth cohort increases each year. [8]

- "Constrictive" pyramid or Declining population

- A population pyramid that is narrowed at the bottom. The population is generally older on average, as the country has long life expectancy, a low death rate, but also a low birth rate.[6] This may suggest that in future there may be a high dependency ratio due to reducing numbers at working ages. This is a typical pattern for a very developed country, with a high level of education, easy access to and incentive to use birth control, good health care, and few negative environmental factors.[9]

-

Population pyramid of Afghanistan (Expansive)

-

Population pyramid of Ecuador (Stationary)

-

Population pyramid of Italy (Constrictive)

-

Population pyramid of Qatar (Unbalanced)

Youth bulge

[edit]

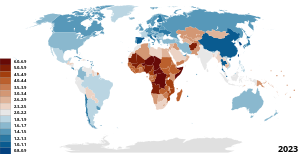

Gary Fuller (1995) described a youth bulge as a type of expansive pyramid. Gunnar Heinsohn (2003) argues that an excess in especially young adult male population predictably leads to social unrest, war, and terrorism, as the "third and fourth sons" that find no prestigious positions in their existing societies rationalize their impetus to compete by religion or political ideology.

Heinsohn claims that most historical periods of social unrest lacking external triggers (such as rapid climatic changes or other catastrophic changes of the environment) and most genocides can be readily explained as a result of a built-up youth bulge.[10] This factor has been also used to account for the Arab Spring events and the rise of extremist populism in the 2010s.[11] Economic recessions, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s and the late 2000s Great Recession, are also claimed to be explained in part due to a large youth population who cannot find jobs.[11] Youth bulge can be seen as one factor among many in explaining social unrest and uprisings in society.[12] A 2016 study finds that youth bulges increase the chances of non-ethnic civil wars, but not ethnic civil wars.[13]

A large population of adolescents entering the labor force and electorate strains at the seams of the economy and polity, which were designed for smaller populations. This creates unemployment and alienation unless new opportunities are created quickly enough – in which case a 'demographic dividend' accrues because productive workers outweigh young and elderly dependents. Yet the 16–29 age range is associated with risk-taking, especially among males. In general, youth bulges in developing countries are associated with higher unemployment and, as a result, a heightened risk of violence and political instability.[14][15] For Cincotta and Doces (2011), the transition to more mature age structures is almost a sine qua non for democratization.[16]

To reverse the effects of youth bulges, specific policies such as creating more jobs, improving family planning programs, and reducing over all infant mortality rates should be a priority.[17]

-

Population pyramid of Egypt in 2005. Many of those 30 and younger are educated citizens who are experiencing difficulty finding work.

-

Nearly half of Libya's 2011 population consists of people younger than age 20.

Middle East and North Africa

[edit]The Middle East and North Africa are currently experiencing a prominent youth bulge. "Across the Middle East, countries have experienced a pronounced increase in the size of their youth populations over recent decades, both in total numbers and as a percentage of the total population. Today, the nearly 111 million individuals aging between 15 to 29 living across the region make up nearly 27 percent of the region's population."[18] Structural changes in service provision, especially health care, beginning in the 1960s created the conditions for a demographic explosion, which has resulted in a population consisting primarily of younger people. It is estimated that around 65% of the regional population is under the age of 25.[19]

The youth bulge in the Middle East and North Africa has been favorably compared to that of East Asia, which harnessed this human capital and saw huge economic growth in recent decades.[20] The youth bulge has been referred to by the Middle East Youth Initiative as a demographic gift, which, if engaged, could fuel regional economic growth and development.[21] "While the growth of the youth population imposes supply pressures on education systems and labor markets, it also means that a growing share of the overall population is made up of those considered to be of working age; and thus not dependent on the economic activity of others. In turn, this declining dependency ratio can have a positive impact on overall economic growth, creating a demographic dividend. The ability of a particular economy to harness this dividend, however, is dependent on its ability to ensure the deployment of this growing working-age population towards productive economic activity, and to create the jobs necessary for the growing labor force."[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Population Pyramids of the World from 1950 to 2100". PopulationPyramid.net. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Weeks, John (2001). Population An introduction to concepts and issues. Wadsworth. p. 307.

- ^ "population pyramid | sociology". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ^ Department of Health Home Archived 2009-08-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "From Population Pyramids to Pillars". www.prb.org. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ^ a b c Population Pyramids - Oregon State University

- ^ Weeks, John (2011). Population An Introduction to concepts and issues. Wadsworth. p. 309. ISBN 978-1305094505.

- ^ Korenjak-Cˇ erne, Kejžar, Batagelj (2008). "Clustering of Population Pyramids". Informatica. 32.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boucher, Lauren (10 March 2016). "What are the different types of population pyramids?". www.populationeducation.org. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Why a two-state solution doesn't guarantee peace in the Middle East". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ^ a b Korotayev A. et al.A Trap At The Escape From The Trap? Demographic-Structural Factors of Political Instability in Modern Africa and West Asia. Cliodynamics 2/2 (2011): 1-28.

- ^ "The Effects of 'Youth Bulge' on Civil Conflicts". Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Yair, Omer; Miodownik, Dan (2016-02-01). "Youth bulge and civil war: Why a country's share of young adults explains only non-ethnic wars". Conflict Management and Peace Science. 33 (1): 25–44. doi:10.1177/0738894214544613. ISSN 0738-8942. S2CID 144349983.

- ^ Huntington, Samuel P. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster

- ^ Urdal, Henrik. 2006. "A Clash of Generations? Youth Bulges and Political Violence." International Studies Quarterly 50:607-29 doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00416.x

- ^ Cincotta, Richard, and John Doces. 2011. "The Age-structural Maturity Thesis: The Youth Bulge's Influence on the Advent and Stability of Liberal Democracy?" In Political Demography: identity, conflict and institutions ed. J. A. Goldstone, E. Kaufmann and M. Toft. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Press Archived 2017-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Effects of 'Youth Bulge' on Civil Conflicts". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ^ a b Hassan, Islam; Dyer, Paul (2017). "The State of Middle Eastern Youth" (PDF). The Muslim World. 107 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1111/muwo.12175.

- ^ "Middle East Youth Initiative". Middle East Youth Initiative. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ "Youth – An Undervalued Asset: Towards a New Agenda in the Middle East and North Africa, Progress, Challenges and Way Forward," Middle East and North Africa Region Human Development Department (MNSHD), The World Bank, 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ "Middle East Youth Initiative: About: Why Shabab?". Retrieved 27 October 2011.

Additional references

[edit]- U.S. Census Bureau, Demographic Internet Staff (June 27, 2011). "International Programs, International Data Base". Information Gateway. U.S. Census Bureau.

- "Population Reference Bureau – Inform, Empower, Advance". Population Reference Bureau.

- "Databases". United Nations.

- Zarulli, Virginia, et al. "Women Live Longer than Men Even During Severe Famines and Epidemics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Sciences, Jan 3 2018.

External links

[edit]- World Population Prospects, the 2010 Revision, Website of the United Nations Population Division with population pyramids for all countries

- U.S. Census Bureau, International Statistical Agencies

- U.S. Census Bureau, International Database (IDB)

- Australian animated population pyramids, Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Interactive population pyramids of metropolitan France 1901-2060 (INSEE)