Edward Bunker

Edward Bunker | |

|---|---|

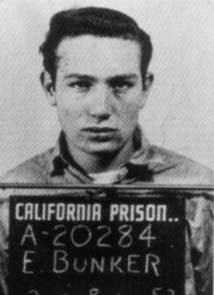

Edward Bunker mugshot taken at San Quentin State Prison in 1952 | |

| Born | Edward Heward Bunker December 31, 1933 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | July 19, 2005 (aged 71) Burbank, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Hollywood Forever, Hollywood, California |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Transgressive fiction |

Edward Heward Bunker[1] (December 31, 1933 – July 19, 2005) was an American author of crime fiction, a screenwriter, convicted felon, and an actor. He wrote numerous books, some of which have been adapted into films. He wrote the scripts for—and acted in—Straight Time (1978) (adapted from his debut novel No Beast So Fierce), Runaway Train (1985), and Animal Factory (2000) (adapted from his sophomore novel of the same name). He also played a minor role in Reservoir Dogs (1992).

He began running away from home when he was five years old, and developed a pattern of criminal behavior, earning his first conviction when he was fourteen, leading to a cycle of incarceration, parole, re-offending, and further jail time.[2] He was convicted of bank robbery, drug dealing, extortion, armed robbery, and forgery.[2] Bunker was released from prison for the last time in 1975, after which he focused on his career as a writer and actor. The character Nate, a career criminal who fences stolen goods in the 1995 heist movie Heat, played by Jon Voight, was based on Bunker, who was consultant to director Michael Mann.

Early life

[edit]1930s–1940s

[edit]Bunker was born on December 31, 1933[1][3] into a troubled family in Los Angeles. His mother, Sarah (née Johnston), was a chorus girl from Vancouver, and his father, Edward N. Bunker, a stage hand.[4][5] His first clear memories were of his alcoholic parents screaming at each other, and police arriving to "keep the peace", a cycle that led to divorce.[6][7]

My parents divorced when I was four and I was put in boarding homes, which I didn't like. I went overnight from being an only child—kind of pampered and spoilt—to a "Lord of the Flies" situation with a lot of boys. I didn't like it and I ran away and rebelled and that set a pattern and the pattern went on.[8]

Consistently rebellious and defiant, young Bunker was subjected to a harsh regime of discipline. He attended a military school for a few months, where he began stealing, and eventually ran away again, ending up in a hobo camp. While Bunker eventually was apprehended by the authorities, this established a pattern he followed throughout his formative years. By age 11, Bunker was picked up by the police and placed in juvenile hall after he assaulted his father.[9] Some sources cite that this incident, along with extreme experiences such as the severe beating he experienced in a state hospital called Pacific Colony (later called Lanterman Developmental Center), created in Bunker a life-long distrust for authority and institutions.[9]

Bunker spent time in the juvenile detention facility Preston Castle in Ione, California, where he became acquainted with hardened young criminals.[6] Although young and small, he was intelligent (with an IQ of 152), streetwise, and extremely literate.[10] A long string of escapes, problems with the law, and different institutions—including a mental hospital—followed.[6]

At the age of fourteen, following his first criminal conviction, Bunker was paroled to the care of his aunt. However, two years later he was caught on a parole violation, and was this time sent to adult prison. In Los Angeles County Jail, he claimed[4] that he stabbed convicted murderer Billy Cook, although circumstantial evidence from the National Archives shows that Bunker and Cook did not have overlapping stays there. Some thought he was unhinged, but in Bunker's book Mr. Blue: Memoirs of a Renegade he stated this behavior was a ruse designed to make people leave him alone.[6]

Criminal life and early writing

[edit]1950s–1960s

[edit]In 1950, while at the McKinley Home for Boys, Bunker met one of the home's prominent benefactors, Louise Fazenda, a star of the silent screen and wife of the producer Hal B Wallis, who gave him support and encouragement.[11] Through her he met Aldous Huxley, Tennessee Williams, and newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, whose guest he was at San Simeon.[12][7] Fazenda sent him a portable typewriter, a dictionary, a thesaurus, and a subscription to the Sunday edition of The New York Times, whose Book Review he devoured. He also subscribed to Writer’s Digest and enrolled in a correspondence course in freshman English from the University of California, selling blood to pay for the postage.[11] However, the following year the 17-year-old Bunker had the dubious honor of being the youngest-ever inmate in San Quentin State Prison.[13]

The first time I was in San Quentin I was there for just about five years and I read five books a week that whole time. Every Saturday morning I'd go to the library and I could check out five books. I read history, fiction, psychology, philosophy...everything.[8]

During his time spent in solitary confinement, Bunker was near the cell of death row inmate Caryl Chessman, who was writing his memoir Cell 2455, Death Row. Chessman had sent Bunker an issue of Argosy magazine, in which the first chapter of his book was published; in 1955 the memoir was made into a movie by Fred F. Sears. Bunker—who had dropped out of school in seventh grade—said that Chessman, along with other prison writers including Dostoevsky and Cervantes, inspired him to become a writer himself.[11][12]

Bunker was paroled in 1956. Now 22, he was unable to adjust to living in normal society. As an ex-convict, he felt ostracized by "normal" people, although he managed to stay out of trouble for several years. Although Fazenda attempted to help him, after she was diagnosed with a nervous breakdown her husband pronounced many of her former friends—including Bunker—personae non-gratae in the Wallis household. Bunker held down various jobs for a while, including that of a used car salesman, but eventually returned to crime. He orchestrated robberies (without personally taking part in them), forged checks, and engaged in other criminal activities.[14]

Bunker ended up back in jail for 90 days on a misdemeanor charge. He was sent to a low-security state work farm but escaped almost immediately. After more than a year, he was arrested after a failed bank robbery and high-speed car chase. Pretending to be insane (faking a suicide attempt and claiming that the Catholic Church had inserted a radio into his head), he was declared criminally insane.[14]

1970s

[edit]Although Bunker eventually was released, he continued a life of crime. In the early 1970s, Bunker ran a profitable drug racket in San Francisco; he was arrested again when the police, who had put a tracking device on his car, followed him to a bank heist. (The police expected Bunker to lead them to a drug deal and were rather shocked by their stroke of luck.) Bunker expected a 20-year sentence, but thanks to the solicitations of influential friends and a lenient judge, got only five.[14]

In the early 1970s he was a criminal associate of Sandra Good and Lynette Fromme.[15]

Career

[edit]No Beast So Fierce and early success

[edit]In prison, Bunker continued to write. While still incarcerated, he finally had his first novel No Beast So Fierce published in 1973, to which Dustin Hoffman purchased the film rights.[3] Novelist James Ellroy said it was "quite simply one of the great crime novels of the past 30 years: perhaps the best novel of the LA underworld ever written".[2] Bunker was paroled in 1975, having spent 18 years of his life in various institutions. While he was still tempted by crime, he now found himself earning a living from writing and acting. He felt that his criminal career had been forced by circumstances; now that those circumstances had changed, he could stop being a criminal.[14]

Animal Factory and film work

[edit]He published his second novel, Animal Factory to favorable reviews in 1977. The following year saw the release of Straight Time, a film-adaptation of No Beast So Fierce. While it was not a commercial success, it earned positive reviews and Bunker got his first screenwriting and acting credits.[16][17] Like most of the roles Bunker played, it was a small part, and he went on to appear in numerous movies, such as The Running Man, Tango & Cash and Reservoir Dogs, as well as the film version of Animal Factory, in 2000, for which he also wrote the screenplay. In 1985, he had written the screenplay for Runaway Train, in which he had a small part, as did Danny Trejo thanks to Bunker's help; the two had known each other when they were incarcerated together years before.[18] The film helped launch Trejo's career.[19] An obituary in the Los Angeles Times described Bunker's appearance onscreen:

With his soft, raspy voice, a nose broken in innumerable fights and a scar from a 1953 knife wound that ran from his forehead to his lip, the compact and muscular ex-con was ideal for typecasting as a big-screen thug.[11]

In Reservoir Dogs, he played Mr. Blue, one of two criminals killed during a heist.[20] The film's director, Quentin Tarantino, had studied Straight Time while attending Robert Redford's Sundance Institute.[6] Bunker was the inspiration for Nate, Jon Voight's character in Michael Mann's 1995 crime film Heat; Bunker also worked as an adviser on the film.[6][7] In The Long Riders, he had a brief role as Bill Chadwell, one of two members of the James-Younger Gang killed during a bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota.[21]

Prior to his death, Bunker assisted in production of short films alongside Canadian director Sudz Sutherland such as "The Confessions of a Taxicab Man", "The Spooky House on Lundy's Lane", and "Angie's Bang". He also wrote and directed a Molson Canadian Cold Shot commercial.[22]

Writing style

[edit]Bunker's hard-boiled and unapologetic crime novels are informed by his personal experiences in a society of criminals in general and by his time in the penal system in particular. Little Boy Blue, in particular, draws heavily on Bunker's own life as a young man. He recounted in an interview, "It has always been as if I carry chaos with me the way others carry typhoid. My purpose in writing is to transcend my existence by illuminating it."[23] A common theme in his fiction is that of men being sucked into a circle of crime at a very young age and growing up in a vicious world where authorities are at worst cruel and at best incompetent and ineffectual, and those stuck in the system can be either abusers or helpless victims, regardless of whether they are in jail or outside. Recounting Bunker's piece "The Inhuman Zoo" for West Magazine, Dennis McLellan wrote:

Deputies in Central Jail sometimes stomped inmates for no reason. [Bunker] gave examples of their pervasive and almost casual willingness to abuse the poor and minorities, and to step over an invisible line into brutality: To young men—very young—unaccustomed to power, and who tend to be authoritarian, the line is lost in the intoxication of having total control over human beings whom they see as animals.[11]

Bunker said that much of his writing was based on actual events and people he has known.

I write about criminals. That's what—you know, Dostoyevsky wrote—I mean, you know, after he went to prison for seven years, that's what he wrote about, you know. That's what they tell you—you know, rule number one of creative writing: "Write about what you know."[24]

In Bunker's work, there is often an element of envy and disdain towards the normal people who live outside of this circle and hypocritically ensure that those caught in it have no way out. Most of Bunker's characters have no qualms about stealing or brutalizing others and, as a rule, they prefer a life of crime over an honest job, in great part because the only honest career options are badly paying and low-class jobs in retail or manual labor.

[Bunker] focuses with cold honesty on parts of town and types of people that many Southern Californians are oblivious to or ignore. His face, liberally etched by countless brawls in juvenile hall, reform school, jail and prison, matches the hard-edged places his books describe.[11]

Bunker's autobiography, Mr. Blue: Memoirs of a Renegade, was published in 1999.

Personal life and death

[edit]In 1977, Bunker married a young real estate agent, Jennifer Steele.[11] In 1993, a son, Brendan, was born. The marriage ended in divorce.

Bunker was close friends with Mexican Mafia leader Joe "Pegleg" Morgan, and San Francisco State University professor John Irwin, as well as actor Danny Trejo, who is the godfather of his son. He first met all three men while serving time in Folsom State Prison.[25]

A diabetic, Bunker died on July 19, 2005, at Providence St. Joseph Medical Center in Burbank, California, following surgery to improve the circulation in his legs. He was 71. The news of Bunker's death was broken by his lifelong friend, screenwriter Robert Dellinger. The two had met in 1973 at the federal prison on Terminal Island, where Dellinger taught a creative writing class.[11]

Filmography

[edit]- 1978 Straight Time as Mickey (also co-screenwriter, based on his novel No Beast So Fierce)

- 1980 The Long Riders as Bill Chadwell

- 1985 Runaway Train as Jonah (also co-screenwriter)

- 1986 Slow Burn as George

- 1987 Shy People as Chuck

- 1987 The Running Man as Lenny

- 1988 Miracle Mile as The Nightwatchman

- 1988 Fear as Lenny

- 1989 Relentless as Cardoza

- 1989 Best of the Best as Stan

- 1989 Tango & Cash as Captain Holmes

- 1992 Reservoir Dogs as "Mr. Blue"

- 1993 Best of the Best 2 as Spotlight Operator

- 1993 Distant Cousins as Mr. Benson

- 1993 Love, Cheat & Steal as Old Con

- 1994 Somebody to Love as Jimmy

- 1996 Caméléone as Sid Dembo

- 1998 Shadrach as Joe Thorton

- 2000 Animal Factory as Buzzard (also co-screenwriter, based on his novel)

- 2001 Family Secrets as Douglas Marley

- 2002 13 Moons as Hoodlum #1

- 2005 The Longest Yard as "Skitchy" Rivers

- 2005 Nice Guys (AKA: High Hopes) as Joe "Big Joe"

- 2010 Venus & Vegas Micky, The Calc (filmed in 2004; released posthumously) (final film role)

Books

[edit]- No Beast So Fierce (1973)

- The Animal Factory (1977)

- Little Boy Blue (1981)

- Dog Eat Dog (1995)

- Mr. Blue: Memoirs of a Renegade (1999)—issued in the U.S. as Education of a Felon (2000)

- Stark (2006)

- Death Row Breakout and Other Stories (2010)—published posthumously

References

[edit]- ^ a b Wilson, Scott (2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons (3 ed.). McFarland & Company. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-7864-7992-4.

- ^ a b c "Edward Bunker". The Independent. July 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Dellinger, Robert (October 1, 2000). "Edward Bunker remembers his first sentence. he wrote from the heart. And from experience: 'Two boys went to rob a liquor store.'". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Bunker, Edward (August 2001). Education of a Felon: A Memoir. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 55. ISBN 0-312-28076-9.

- ^ Edward Bunker Biography (1933–)

- ^ a b c d e f "No Beast So Fierce: The Book That Got a Man Released from Prison". July 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Obituary: Edward Bunker". TheGuardian.com. July 30, 2005.

- ^ a b "Mr Blue—Edward Bunker". RTÉ.ie. March 2001.

- ^ a b Powell, Steven (2012). 100 American Crime Writers. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 41. ISBN 9780230525375.

- ^ Mr Blue: Memoirs of a Renegade, 2012, "No Exit: Author's details"

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Edward Bunker, 71; Ex-Con Wrote Realistic Novels About Crime". Los Angeles Times. July 24, 2005.

- ^ a b "Edward Bunker | No Exit Press".

- ^ Baime, Albert. Review of Education of a Felon: A Memoir. Accessed January 27, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Waring, Charles (September 1, 2000). "Born Under a Bad Sign — The Life of Edward Bunker". Crime Time. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Bravin, Jess (May 15, 1997). Squeaky: The Life and Times of Lynette Alice Fromme. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312156634.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (March 22, 1978). "Hoffman plays it straight again; this time it's a superior thriller". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 7

- ^ Canby, Vincent (March 18, 1978). "'Straight Time' a Film of Grim Wit". The New York Times. 14.

- ^ "Danny Trejo: 'I went to the hole looking at three gas-chamber offences'". TheGuardian.com. December 6, 2012.

- ^ "'Machete' star Danny Trejo is an illustrated man, in many ways - USATODAY.com". usatoday30.usatoday.com. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ Connolly, John; Burke, Declan (2016). Books to Die For: The World's Greatest Mystery Writers on the World's Greatest Mystery Novels. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 297. ISBN 9781451696578.

- ^ "Edward Bunker". Variety. July 19, 2005. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Tyler, Adrienne (January 3, 2023). "Reservoir Dogs Team Member Was Involved In A Real Life Robbery". Screen Rant. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ "Edward Bunker, Ex-Convict and Novelist, Is Dead at 71". The New York Times. Associated Press. July 27, 2005. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ "Prison Novelist Edward Bunker". NPR.org.

- ^ Hernandez, Daniel. "Trejo's full circle". Retrieved February 19, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Edward Bunker (2000). Education of a Felon: A Memoir. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-25315-X.

External links

[edit]- 1933 births

- 2005 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- American bank robbers

- American convicts who became writers

- American crime fiction writers

- American drug traffickers

- American escapees

- American extortionists

- American male film actors

- American male novelists

- American male screenwriters

- American people convicted of robbery

- American people convicted of theft

- Burials at Hollywood Forever Cemetery

- Criminals from California

- Forgers

- Male actors from Los Angeles

- Novelists from California

- People from Hollywood, Los Angeles

- Inmates of San Quentin State Prison

- Screenwriters from California

- Writers from Los Angeles