Robin Morgan

Robin Morgan | |

|---|---|

Morgan in 2012 | |

| Born | January 29, 1941 Lake Worth, Florida, U.S. |

| Education | Columbia University (BA) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1940s–present |

| Notable work | Sisterhood anthologies |

| Spouse |

Kenneth Pitchford

(m. 1962–1983) |

| Children | Blake Morgan |

| Website | robinmorgan |

Robin Morgan (born January 29, 1941) is an American poet, writer, activist, journalist, lecturer and former child actor. Since the early 1960s, she has been a key radical feminist member of the American Women's Movement, and a leader in the international feminist movement. Her 1970 anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful was cited by the New York Public Library as "One of the 100 Most Influential Books of the 20th Century.".[1] She has written more than 20 books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, and was editor of Ms. magazine.[2]

During the 1960s, she participated in the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements; in the late 1960s, she was a founding member of radical feminist organizations such as New York Radical Women and W.I.T.C.H. She founded or co-founded the Feminist Women's Health Network, the National Battered Women's Refuge Network, Media Women, the National Network of Rape Crisis Centers, the Feminist Writers' Guild, the Women's Foreign Policy Council, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Sisterhood Is Global Institute, GlobalSister.org, and Greenstone Women's Radio Network. She also co-founded the Women's Media Center with activist Gloria Steinem and actor/activist Jane Fonda. In 2018, she was listed as one of BBC's 100 Women.[3]

Child actor

[edit]

Due to circumstances at her birth, her mother claimed that Robin Morgan was born a year later than she actually was[4] (see birth and parents), and throughout her career as a child actor, she was thought to be a year younger than she actually was, both by herself and others.

Already as a toddler, her mother, Faith, and mother's sister Sally started Robin as a child model. At the age of five, believed to be four,[4] she got her own program, titled Little Robin Morgan, on the New York radio station WOR. She was also a regular on the original network radio version of Juvenile Jury. Her acting career took off when she was eight and started in the TV series Mama, as Dagmar Hansen, the younger sister in the family depicted in the series. The show premiered on CBS in 1949, starring Peggy Wood, and was a great success. Morgan played Cecchina Cabrini in Citizen Saint (1947).

During the Golden Age of Television, Morgan starred in such "TV spectaculars" as Kiss and Tell and Alice in Wonderland, and guest starred on such live dramas as Omnibus, Suspense, Danger, Hallmark Hall of Fame, Robert Montgomery Presents, Tales of Tomorrow, and Kraft Theatre. She worked with directors such as Sidney Lumet, John Frankenheimer, Ralph Nelson; writers such as Paddy Chayefsky and Rod Serling; and performed with actors such as Boris Karloff, Rosalind Russell, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, and Cliff Robertson.[4]

Having wanted to write rather than to act since she was four, Morgan fought her mother's efforts to keep her in show business,[5] and left the cast of Mama at age 14.

Adult life and career

[edit]As she entered adulthood, Robin Morgan continued her education as a non-matriculating student at Columbia University. She began working as a secretary at Curtis Brown Literary Agency, where she met and worked with such writers as poet W. H. Auden in the early 1960s. She had already begun publishing her own poetry (later collected in her first book of poems, Monster, published in 1972). Throughout the next decades, along with political activism, writing fiction and nonfiction prose, and lecturing at colleges and universities on women's rights, Morgan continued to write and publish poetry.[4]

In 1962, Morgan married poet Kenneth Pitchford.[5] She gave birth to their son, Blake Morgan, in 1969. The couple divorced in 1983.[6] At that time, she was working as an editor at Grove Press and was involved in an attempt to unionize the publishing industry. When Grove summarily fired her and other union sympathizers, she led a seizure and occupation of their offices in the spring of 1970, protesting the union-busting, as well as the dishonest accounting of royalties to Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X's widow. Morgan and eight other women were arrested that day.[4]

In the mid-1970s Morgan became a Contributing Editor to Ms. magazine, and continued her affiliation there as a part- or full-time editor in the following decades. She served as editor-in-chief of the magazine from 1989 to 1994, turning it into a highly successful, ad-free, bimonthly, international publication, which won awards for both writing and design, and received considerable acclaim among journalists.[7][8]

In 1979, when the Supersisters trading card set was produced and distributed, featuring famous women from politics, media and entertainment, culture, sports, and other areas of achievement, one of the cards featured Morgan's name and picture.[9] Today, the trading cards are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the University of Iowa library.[10]

In 2005, Morgan co-founded the non-profit progressive women's media organization, The Women’s Media Center, with friends actor/activist Jane Fonda, and activist Gloria Steinem. Seven years later, in 2012, she debuted a weekly radio show and podcast, Women’s Media Center Live With Robin Morgan. The broadcast is syndicated in the US and, as a podcast, is published online at the WMCLive website, and distributed on iTunes in 110 countries. It has been praised by The Huffington Post as "talk radio with a brain" and features commentary by Morgan about recent news, and interviews with activists, politicians, authors, actors and artists.[11] The weekly hour was picked up by CBS Radio two weeks after its launch and is broadcast on CBS affiliate WJFK each Saturday. The program features commentary by Morgan about recent news, and interviews with activists, politicians, authors, actors and artists.

Activism

[edit]By 1962 Morgan had become active in the anti-war Left, and had also contributed articles and poetry to such Left-wing and counter-culture journals as Liberation, Rat, Win, and The National Guardian.[4]

In the 1960s she became increasingly involved in social-justice movements, notably the civil-rights and anti-Vietnam war. In early 1967, she was active in the Youth International Party (known in the media as the "Yippies"), with Abbie Hoffman and Paul Krassner. However, tensions over sexism within the YIP (and the New Left in general) came to a head when Morgan grew more involved in Women's Liberation and contemporary feminism.[4]

In 1967, Morgan became a founding member of the short-lived New York Radical Women group. She was the key organizer of their September 1968 inaugural protest of the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City.[10] Morgan wrote the Miss America protest pamphlet No More Miss America!, and that same year cofounded Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (W.I.T.C.H.), a radical feminist group that used public street theater (called "hexes" or "zaps") to call attention to sexism. Morgan designed the universal symbol of the women’s movement––the female symbol, a circle with a cross beneath, centered with a raised fist. The Oxford English Dictionary also credits her with first using the term "herstory" in print in her 1970 anthology Sisterhood is Powerful.[12][13] Concerning the feminist organization W.I.T.C.H., Morgan wrote:

- The fluidity and wit of the witches is evident in the ever-changing acronym: the basic, original title was Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell [...] and the latest heard at this writing is Women Inspired to Commit Herstory."[12]

With the royalties from her anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful, Morgan founded the first feminist grant-giving foundation in the US: The Sisterhood Is Powerful Fund, which provided seed money to many early women's groups throughout the 1970s and 1980s. She made a decisive break from what she described as the "male Left"[14] when she led the women's takeover of the underground newspaper Rat in 1970,[15] and listed the reasons for her break in the first women's issue of the paper, in her essay titled "Goodbye to All That". The essay gained notoriety in the press for naming specific sexist men and institutions in the Left. Decades later, during the Democratic primaries for the 2008 presidential race, Morgan wrote a fiery sequel to her original essay, titled "Goodbye To All That #2", in defense of Hillary Clinton.[4] The article quickly went viral on the internet for lambasting sexist rhetoric directed towards Clinton by the media.[15]

In 1977, Morgan became an associate of the Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP).[16] WIFP is an American nonprofit publishing organization. The organization works to increase communication between women and connect the public with forms of women-based media.

Morgan has traveled extensively across the United States and around the world to bring attention to cross-cultural sexism. She has met with and interviewed female rebel fighters in the Philippines, Brazilian women activists in the slums/favelas of Rio, women organizers in the townships of South Africa, and underground feminists in Iran.[10] Twice––in 1986 and 1989 she spent months in the Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, West Bank, and Gaza, to report on the conditions of women. Morgan has also spoken at universities and institutions in countries across Europe, the Caribbean, and Central America, as well as in Australia, Brazil, China, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Nepal, New Zealand, Pacific Island nations, the Philippines, and South Africa.[7]

Over the years, Morgan has received numerous awards for her activism on women’s rights.[10] The Feminist Majority Foundation named Robin Morgan "Woman of the Year" in 1990; she received the Warrior Woman Award for Promoting Racial Understanding from The Asian American Women's National Organization in 1992; in 2002 she received a Lifetime Achievement in Human Rights from Equality Now, and in 2003 The Feminist Press gave her a "Femmy" Award for her "service to literature".[7] She has also received the Humanist Heroine Award from The American Humanist Association in 2007.[17]

- Limbaugh FCC incident

In March 2012 Morgan, along with her Women's Media Center co-founders Jane Fonda and Gloria Steinem, wrote an open letter asking listeners to request that the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) investigate the Rush Limbaugh–Sandra Fluke controversy, where Rush Limbaugh referred to Sandra Fluke as a "slut" and "prostitute" after she advocated for insurance coverage for contraception.[18] They asked that stations licensed for public airwaves carrying Limbaugh be held accountable for contravening public interest as a continual promoter of hate speech against various disempowered and minority groups.[19]

Sisterhood anthologies

[edit]

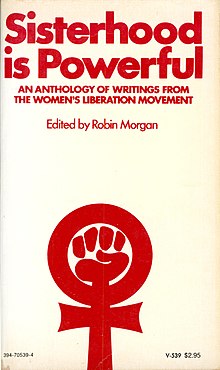

In 1970, Morgan compiled, edited, and introduced the first anthology of feminist writings, Sisterhood is Powerful. The compilation included now-classic feminist essays by such activists as Naomi Weisstein, Kate Millett, Eleanor Holmes Norton, Florynce Kennedy, Frances M. Beal, Joreen, Marge Piercy, Lucinda Cisler and Mary Daly, as well as historical documents including the N.O.W. Bill of Rights, excerpts from the SCUM Manifesto, the Redstockings Manifesto, historical documents from W.I.T.C.H., and a germinal statement from the Black Women’s Liberation Group of Mount Vernon.[20] It also included what Morgan called "verbal karate": useful quotes and statistics about women.[21] The anthology was cited by the New York Public Library as one of the “New York Public Library's Books of the [20th] Century”.[1] Morgan established the first American feminist grant-giving organization, The Sisterhood Is Powerful Fund, with the royalties from Sisterhood Is Powerful.[22] However, the anthology was banned in Chile, China, and South Africa.[22]

Her follow-up volume in 1984, Sisterhood Is Global: The International Women's Movement Anthology, compiled articles about women in over seventy countries. That same year she founded the Sisterhood Is Global Institute, notable for being the first international feminist think tank. Repeatedly refusing the post of president, she was elected secretary of the organization from 1989 to 1993, was VP from 1993 to 1997, and after serving on the advisory board, finally agreed to become president in 2004.[23] A third volume, Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women's Anthology for a New Millennium in 2003, was a collection of articles mostly by well-known feminists, both young and "vintage", in a retrospective on and future blueprint for the feminist movement.[10] It was compiled, edited, and with an introduction by Morgan, and Morgan wrote "To Vintage Feminists" and "To Younger Women", which were both included in the anthology as Personal Postscripts.[24]

Journalism

[edit]Morgan's articles, essays, reviews, interviews, political analyses, and investigative journalism have appeared widely in such publications as The Atlantic, Broadsheet, Chrysalis, Essence, Everywoman, The Feminist Art Journal, The Guardian (US), The Guardian (UK), The Hudson Review, the Los Angeles Times, Ms., The New Republic, The New York Times, Off Our Backs, Pacific Ways, The Second Wave, Sojourner, The Village Voice, The Voice of Women, and various United Nations periodicals, etc.

Articles and essays have also appeared in reprint in international media, in English across the Commonwealth, and in translation in 13 languages in Europe, South America, the Middle East, and Asia.[25]

Morgan has served as a contributing editor to Ms. magazine for many years, receiving the Front Page Award for Distinguished Journalism for her cover story titled "The First Feminist Exiles from the USSR" in 1981.[26] She served as the magazine's editor-in-chief from 1989 to 1994, re-launching it as an ad-free, international bimonthly publication in 1991. This earned her a series of awards,[8][27] including the award for Editorial Excellence by Utne Reader in 1991, and the Exceptional Merit in Journalism Award by the National Women's Political Caucus.[7] Morgan resigned her post in 1994 to become Consulting Global Editor of the magazine, which she remains to this day.[28]

Morgan has written for online audiences and blogged frequently. Among her best known articles are "Letters from Ground Zero" (written and posted after the September 11 attacks in 2001 — which went viral), "Goodbye To All That #2", "Women of the Arab Spring", "When Bad News is Good News: Notes of a Feminist News Junkie", "Manhood and Moral Waivers", and "Faith Healing: A Modest Proposal on Religious Fundamentalism". Her online work is hosted in the archives of the Women's Media Center.[25]

Authorship

[edit]

Robin Morgan has published 21 books, including works of poetry, fiction, and the now-classic anthologies Sisterhood Is Powerful, Sisterhood Is Global, and Sisterhood Is Forever.[25] Well before she was known as a feminist leader, literary magazines published her as a serious poet.[29] According to a 1972 review of her first book of poems, Monster, in The Washington Post: "[These poems] establish Morgan as a poet of considerable means. There is a savage elegance, a richness of vocabulary, a thrust and steely polish..... A powerful, challenging book."[25] In 1979 Morgan received a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship in poetry,[29] then held a writing residency at the arts colony Yaddo the following year. During this time she worked on a cycle of verse plays.[30]

Morgan’s poetry collections include A Hot January: Poems 1996–1999 (W. W. Norton, 1999), Depth Perception: New Poems and a Masque (Doubleday, 1994), Upstairs in the Garden: Poems Selected and New 1968–1988 (W. W. Norton, 1990), Death Benefits (Copper Canyon Press, 1981), Lady of the Beasts (Random House, 1976), and Monster (Random House, 1972). Of the book A Hot January, Alice Walker wrote: "Morgan proves that exquisite poetry can be the most surprising gift of grief. A volume as proud, fierce, vulnerable, and brave as the poet herself."[31] A review of Upstairs in the Garden, noted: "As a vindication and celebration of the female experience, these inventive poems successfully wed feminist rhetoric with vivid imagery and sensitivity to the music of language."[32] Two books of poems, Lady of the Beasts and Depth Perception, earned reviews in Poetry Magazine with critic Jay Parini stating that "Robin Morgan will soon be regarded as one of our first-ranking poets."[33]

Morgan had published three books of fiction as of 2015. Her debut novel was the semi-autobiographical Dry Your Smile (published by Doubleday & Company, 1987), followed by The Mer-Child: A Legend for Children and Other Adults (published by The Feminist Press at City University of New York, 1991). Her most recent work of fiction is a historical novel titled The Burning Time (Melville House Books, 2006), set in the 14th century, based on court records of the first witchcraft trial in Ireland.[34] The Burning Time was placed on the Recommended Quality Fiction List of 2007 by the American Library Association,[35] in addition to being the 2006 Paperback Pick by Book Sense (The American Booksellers Association).[34]

Morgan has compiled, edited, and introduced several influential anthologies: Sisterhood Is Powerful: The Women’s Liberation Anthology (1970), Sisterhood Is Global: The International Women’s Movement Anthology (1984), and Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women’s Anthology for a New Millennium (2003). She has herself written non-fiction, including Going Too Far (1978), The Anatomy of Freedom (1984), The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism (1989), The Word of a Woman (1994), and Saturday’s Child: A Memoir (2001). One of the most widely translated of Morgan’s books and a best-seller, The Demon Lover is a commentary on the psychological and political roots of terrorism, and New York Times Book Review called it "Important...compelling....[Morgan] is intense and at times magnificent."[36] Her most recently published book of non-fiction is Fighting Words: A Tool Kit for Combating the Religious Right (2006).[37]

Organizations

[edit]The Sisterhood Is Global Institute

[edit]In 1984, Morgan, together with the late Simone de Beauvoir of France, and women from 80 other countries, founded The Sisterhood Is Global Institute (SIGI), an international non-profit NGO with consultative status to the United Nations, which has for three decades functioned as the world’s first feminist think-tank. The Institute has played a leading policy-formulation, strategic, and activist role in the evolution of the international Women’s Movement. SIGI has also developed a global communications network through which an umbrella of NGO interest, advice, contacts, and support is collectively mobilized to empower the global women’s movement.

Among its many activities, the Institute pioneered the first Urgent Acton Alerts regarding women’s rights; the first Global Campaign To Make Visible Women’s Unpaid Labor In National Accounts; and the first Women’s Rights Manuals For Muslim Societies (in 12 languages). Its most recent project is Donor Direct Action (donordirectaction.org), which links front-line women’s rights activists around the world to money, visibility, and popular support: minimum bureaucracy, maximum impact.

Women’s Media Center

[edit]In 2005, Morgan co-founded the non-profit progressive organization, The Women’s Media Center with her friends actor/activist Jane Fonda, and activist Gloria Steinem. The focus of the organization is to make women powerful and visible in the media.

Lectures and professorships

[edit]An invited speaker at numerous universities in North America, Morgan has traveled—as organizer, speaker, journalist—across North America, Europe, and the Middle East to Australia, Brazil, the Caribbean, Central America, China, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Nepal, New Zealand, Pacific Island nations, the Philippines, and South Africa.[28] She has also been a guest professor or scholar in residence at a variety of academic institutions. She was guest chair for feminist studies at the New College of Florida in 1971; a visiting professor at The Center for Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture at Rutgers University in 1987; a distinguished visiting scholar in residence for literary and cultural studies at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand in 1989; a visiting professor in residence at the University of Denver, Colorado in 1996; and visiting professor at the Center for Documentation on Women at University of Bologna, Italy, in 1996.[7] She was awarded an honorary degree as a Doctor of Humane Letters by the University of Connecticut at Storrs in 1992.[7] The Robin Morgan Papers, a collection that documents the personal, political, and professional aspects of Morgan's life, are archived at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture at Duke University.[7] They date from the 1940s to the present.

Criticism

[edit]Robin Morgan has been arrested, and has received death threats from both the Right and the Left because of her activism.[38] According to a New Yorker magazine article published in the aftermath of Morgan's essay "Goodbye to All That" (#2) going viral on the Internet, "At five feet tall Morgan is, not for the first time, the little woman who has started a big war." In her original essay, "Goodbye to All That" (1970), Morgan bade adieu to "the dream that being in the leadership collective will get you anything but gonorrhea," referring to the "male Left". She also asserted that Charles Manson was "only the logical extreme of the normal American male’s fantasy."[39]

Two years later, Morgan published the poem "Arraignment", in which she openly accused Ted Hughes of the battery and murder of Sylvia Plath.[40][41] There were lawsuits, Morgan's 1972 book Monster which contained that poem was banned, and underground, pirated feminist editions of it were published.[29]

As the leading organizer of the 1968 protest of the Miss America Pageant, "No More Miss America!", Morgan attacked the pageant’s "ludicrous 'beauty' standards and also accused the pageant of being racist, since at that time no African American woman had been a contestant. In addition––according to Morgan––in sending pageant winners to entertain troops in Vietnam, the women served as "death mascots" in an immoral war. Morgan asked, "Where else could one find such a perfect combination of American values -- racism, militarism, capitalism -- all packaged in one 'ideal' symbol, a woman."[42]

Another controversial quote is from her 1978 book, Going Too Far: The Personal Chronicle of a Feminist, where she stated: "I feel that "man-hating" is an honorable and viable political act, that the oppressed have a right to class-hatred against the class that is oppressing them."[43]

Morgan famously walked off The Tonight Show in 1969 when it screened vintage footage of her as a child actor while she was trying to speak seriously about the first national march against rape. Of the incident, she has been quoted as saying: "Imagine talking about such a subject and having it trivialized like that."[38] In 1974, with her phrase "Pornography is the theory, and rape is the practice" (from her essay "Theory and Practice: Pornography and Rape"), she became a central figure on one of the divisive issues in feminism, particularly among anti-pornography feminists in Anglophone countries.

In 1973, Robin Morgan gave the keynote speech at the West Coast Lesbian Conference, in which she criticized Beth Elliott, a performer and organizer of the conference, for being a transgender woman.[44] In this speech she referred to Elliott as a "transsexual male" and used male pronouns throughout, charging her with being "an opportunist, an infiltrator, and a destroyer-with the mentality of a rapist."[45] At the end of her speech she called for a vote on ejecting Elliott, with over two-thirds voting to allow her to remain, however the minority threatened to disrupt the conference and Elliott chose to leave after her performance to avoid this. The event demonstrated the high tension surrounding transgender women's involvement in the women's movement of the 1970s.[46][47][48]

Personal life

[edit]Robin Morgan grew up in New York, first in Mount Vernon, and later in Manhattan, on Sutton Place. She graduated from The Wetter School in Mount Vernon, in 1956, and was privately tutored from then until 1959.[7] She published her first serious poetry in literary magazines at age 17.[4]

In an article published in the Jewish Women's Archive, Morgan reveals she is of Jewish ancestry, but identifies her religion as Wiccan and/or atheist. She is quoted as saying, "When compelled to define myself specifically in ethnic terms—I have described myself as being European American of Ashkenazic (with a touch of Sephardic) Jewish ancestry. I respect and understand the desire of others to affirm their ethnic roots as central to their identities, but while I’m quite proud of mine, I feel they’re just not particularly central to my identity. I am deeply opposed to all patriarchal religions, including though not limited to Judaism."[49] Morgan continues to tackle topics such as religion, politics and sex in fiery commentaries on her radio show WMC Live with Robin Morgan.[50]

Today Robin Morgan lives in Manhattan.[7] Blake Morgan, her son with ex-husband Kenneth Pitchford, is a musician, recording artist, and founder of New York-based record company ECR Music Group.

In 2000 Norton published Morgan’s memoir, Saturday's Child, in which she wrote candidly about "the shadowy circumstances of her birth; a lifelong, impassioned, love-hate relationship with her mother; her years as a famous child actor and her fight to escape show business to become a serious writer; her marriage to a fiery bisexual poet and how motherhood transformed her life; her years in the civil rights movement, the New Left, and counterculture; her emergence a leader of global feminism; and her love affairs with women as well as men," according to BookNews.com.[51] In her book, "her passion for writing, especially poetry, is vividly conveyed, as is her love and respect for her son, born in 1969," according to The New York Times Book Review.[52]

In April 2013, Morgan announced publicly that she had been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, discussing the diagnosis on her radio show WMC Live with Robin Morgan,[53] revealing that she had been diagnosed in 2010, but that her quality of life was thus far "normal".[54] Since her diagnosis, Morgan has become active with the Parkinson's Disease Foundation (PDF), completing training to become part of the organization's Parkinson's Advocates in Research initiative.[55] In 2014 she was the catalyst and took a leadership role in PDF's new Women and PD initiative, which will seek to better serve women impacted by Parkinson's disease by understanding and resolving gender inequalities in PD research, treatment, and caregiver support.[56] Morgan has also written new poetry inspired by her battle with the disease, and performed a reading of some of the poems as a TED Talk, at the TEDWomen 2015 conference.[57]

Birth and parents

[edit]Her mother, Faith Berkeley Morgan, traveled from her New York residence to Florida to give birth, in order to avoid public scrutiny for her unmarried status.[4] Robin's father, a medical doctor named Mates Morgenstern, did not accompany pregnant Faith on her trip.

Until Morgan was 13 years old, her mother Faith claimed that Robin's father had been killed in World War II.[4] However, Robin overheard conversations between her mother and aunt suggesting her father was alive. When she confronted her mother, Faith changed her story to assert that Robin's father had escaped from one Nazi concentration camp after another, and that she had saved his life by sponsoring his immigration to the United States where he had no family.[4] Not until several years later did Robin get proof that this was also a lie.[4]

Morgan learned the truth, both about her father, who was still alive, and how old she really was, early in 1961.[4] Now a young woman, no longer working in show business, Robin found a listing for the medical practice of an obstetrician, Dr. Mates Morgenstern, in the New Brunswick, New Jersey telephone directory. Suspecting this might be her father, she had sought a meeting with him, without her mother's knowledge, and ultimately paid a surprise visit to his New Jersey office in January 1961.

Morgenstern revealed that he was aware of Robin's fame as a child actor, but had remained firm in his decision to avoid contact with Faith Morgan, having chosen not to see her again after the only time he visited her and the infant Robin.[4] He also told Robin, during their conversation in his medical office, that she in fact was born on January 29, 1941, exactly one year earlier than she thought, and disclosed the copy of her original birth certificate, that he had stored in his office. In order to conceal the out-of-wedlock birth, Faith Morgan had asked her Florida obstetrician to sign an affidavit stating that the birth took place on January 29, 1942.[4]

During the conversation in his office, Morgenstern told his daughter that he first met her mother after his arrival in the United States, more than a year before the United States entered World War II, and that she had had nothing to do with his immigration. He added that he had known Faith only briefly and claimed that she had fantasized their relationship as more important than it was.[4] By the time Morgan met her father he had married and had two sons with a woman he had known since they were both children in Austria. Having been separated by the war, they resumed their relationship after she arrived in the United States not long after Robin was born, which probably also added to Morgenstern's decision to abandon Faith and their daughter.[citation needed]

Morgan only met her father once more, in February 1965 when he invited her and her husband to his New Jersey home.[4] Morgenstern did not want his sons to know that they had a half-sister and Morgan acceded to his request that they tell his two sons that she was "the daughter of an old friend."[4] She refused to do so again, however, and never met him or her two half-brothers again.[4]

Morgan describes the two encounters that she had with her biological father in her autobiography, Saturday's Child: A Memoir.

When Faith Morgan developed Parkinson's disease, in her early 60s,[4] Robin telephoned her biological father to let him know. When she asked if he wanted to say goodbye, he declined.[4] During Faith's illness, her life savings, which consisted of the money Robin had earned in her radio and television career – by then a six-figure sum that had accumulated in the bank – was stolen, by her two elderly home caregivers.[4] Morgan discovered this but ultimately chose not to press charges.[citation needed]

Filmography

[edit]- 1940s

- Citizen Saint: The Life of Mother Cabrini (playing Francesca S. Cabrini as a child)

- The Little Robin Morgan Show as herself (WOR radio show)

- Juvenile Jury as herself

- 1950s

- Mama as Dagmar Hansen

- Kraft Television Theatre's Alice in Wonderland (as Alice)

- Mr. I-Magination (as self)

- Tales of Tomorrow (starring as Lily Massner)[58]

- Kiss and Tell TV Special (starring as Corliss Archer, 1956)

- Other videos and kinescopes in the Robin Morgan Collection at the Paley Center for Media, NYC

- 1980s - 2010s

- Not a Love Story: A Film About Pornography [Feature length Documentary] (as herself) (1981)

- The American Experience TV Documentary (as herself) (2002)

- 1968 TV Documentary with Tom Brokaw (as herself) (2007)

- Interview by Ronnie Eldridge (2007)[59]

- Makers: Women Who Make America on PBS (2013)

Publications

[edit]Poetry

[edit]- 1972: Monster (Vintage, ISBN 978-0-394-48226-2)

- 1976: Lady of the Beasts: Poems (Random House, ISBN 978-0-394-40758-6)

- 1981: Death Benefits: A Chapbook (Copper Canyon, Limited Edition of 200 copies)

- 1982: Depth Perception: New Poems and a Masque (Doubleday, ISBN 978-0-385-17794-8)

- 1999: A Hot January: Poems 1996–1999 (W. W. Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-32106-7)

- 1990: Upstairs in the Garden: Poems Selected and New (W. W. Norton, ISBN 0-393-30760-3)

Nonfiction

[edit]- 1977: Going Too Far: The Personal Chronicle of a Feminist, (Random House, ISBN 0-394-72612-X)

- 1982: The Anatomy of Freedom (W.W. Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-31161-7)

- 1989: The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism (W. W. Norton, ISBN 0-7434-5293-3)

- 2001: The Demon Lover: The Roots of Terrorism (Updated Second Edition, Washington Square Press/Simon & Schuster, Inc., ISBN 978-0743452939)

- 1992: The Word of a Woman (W.W. Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-03427-1)

- 1995: A Woman's Creed (pamphlet), The Sisterhood Is Global Institute

- 2001: Saturday's Child: A Memoir (W. W. Norton, ISBN 0-393-05015-7)

- 2006: Fighting Words: A Toolkit for Combating the Religious Right (Nation Books, ISBN 1-56025-948-5)

Fiction

[edit]- 1987: Dry Your Smile (Doubleday, ISBN 978-0-7043-4112-8)

- 1991: The Mer-Child: A New Legend for Children and Other Adults (The Feminist Press, ISBN 978-1-55861-054-5)

- 2006: The Burning Time (Melville House, ISBN 1-933633-00-X)

Anthologies

[edit]- 1969: The New Woman (Poetry Editor) (Bobbs-Merrill, LCCN 70-125895)

- 1970: Sisterhood is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women's Liberation Movement (Random House, ISBN 0-394-70539-4)

- 1984: Sisterhood Is Global: The International Women's Movement Anthology (Doubleday/Anchor Books; revised, updated edition The Feminist Press, 1996, ISBN 978-1-55861-160-3)

- 2003: Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women's Anthology for a New Millennium (Washington Square Press, ISBN 0-7434-6627-6)

Essays

[edit]- "The politics of sado-masochistic fantasies" in Linden, Robin Ruth (1982). Against sadomasochism: a radical feminist analysis. East Palo Alto, California: Frog in the Well. pp. 109–123. ISBN 9780960362837.

- "Light bulbs, radishes and the politics of the 21st century" in Bell, Diane; Klein, Renate, eds. (1996). Radically speaking: feminism reclaimed. Chicago: Spinifex Press. pp. 5–8. ISBN 9781742193649.

Plays

[edit]- "Their Own Country" (debut performance, Ascension Drama Series, New York, December 10, 1961 at 8:30pm, Church of the Ascension, reception immediately following.)

- "The Duel." A verse play, published as "A Masque" in her book Depth Perception (debut perf. Joseph Papp's New Shakespeare Festival Public Theater, New York, 1979)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Diefendork, Elizabeth (1996). "The New York Public Library's Books of the Century". New York Public Library. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Robin Morgan". eNotes. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ "BBC 100 Women 2018: Who is on the list?". BBC News. November 19, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Morgan, Robin (2001). Saturday's Child: A Memoir'. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-05015-7.

- ^ a b Morgan, Robin (1978). Going Too Far: The Personal Chronicle of a Feminist. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-394-72612-0.

- ^ Langston, Donna (2002). A to Z of American Women Leaders and Activists. New York: Facts on File. p. 156. ISBN 0-8160-4468-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Bio". RobinMorgan.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Rich, Adrienne (December 31, 1972). ""Voices in the Wilderness," in Book World: Review of Monster: Poems". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ Wulf, Steve (March 23, 2015). "Supersisters: Original Roster". Espn.go.com. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Robin Morgan". Jewish Women's Archive. 2005. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ "Women's Media Center Live with Robin Morgan". Wmclive.com. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ a b "Herstory", Oxford English Dictionary Online (Oxford University Press, 2006).

- ^ "Dry Your Smile". Ms. Magazine. March 30, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ "Robin Morgan". Answers.com. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Levy, Ariel (April 21, 2008). "Goodbye Again". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Associates | The Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press". www.wifp.org. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ Willis, Pat (December 2007). "Robin Morgan, 2007 Humanist Heroine". The Humanist. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ Little, Lyneka (March 13, 2012). "Jane Fonda, Gloria Steinem Call For FCC to Ban Rush Limbaugh". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ Morgan, Robin (March 12, 2012). "FCC should clear Limbaugh from airwaves". CNN. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ Brain, Norman (2006). "The Consciousness-Raising Document, Feminist Anthologies, and Black Women in Sisterhood is Powerful". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 27 (3): 38–64. doi:10.1353/fro.2006.a209988. JSTOR 4137384. S2CID 141752970.

- ^ Battle-Sister, Ann (1971). "Review of 'A Tyrant's Plea,' Dominated Man by Albert Memmi; Born Female by Caroline Bird; Sisterhood is Powerful by Robin Morgan". Journal of Marriage and Family. 33 (3): 592–597. doi:10.2307/349862. JSTOR 349862.

- ^ a b Robin Morgan (November 1, 2007). Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women's Anthology for a New Millennium. Simon and Schuster. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-4165-9576-2.

- ^ "Background". The Sisterhood is Global Institute. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Library Resource Finder: Table of Contents for: Sisterhood is forever : the women's anth". Vufind.carli.illinois.edu. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Robin Morgan". Women's Media Center. Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Dry Your Smile". RobinMorgan.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ "The Burning Time". RobinMorgan.us. 2006. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ a b "Robin Morgan | Soapbox Inc". Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c Robin Morgan. "Monster: Poems by Robin Morgan — Reviews, Discussion, Bookclubs, Lists". Goodreads.com. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ "Notes on Contributors". Kalliope: A Journal of Women's Literature and Art. 3 (1): 70. 1980.

- ^ Morgan, Robin (April 14, 2015). "Robin Morgan". Robin Morgan. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- ^ "Author, Activist, Feminist | NYC". Robin Morgan. April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ "Ironic Feminism, Empathic Activism: Robin Morgan's Saturday's Child". Ms. Magazine. March 30, 2001. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ a b "The Burning Time | Robin Morgan | Author, Activist, Feminist | NYC". Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ "Robin Morgan Bio". The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ Morgan, Robin (December 4, 2001). The Demon Lover: The Roots of Terrorism: Robin Morgan: 9780743452939: Amazon.com: Books. Washington Square Press. ISBN 0743452933.

- ^ The Sisterhood Is Global Institute (July 1, 2013). "About | The Sisterhood Is Global Institute". Sigi.org. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ a b "Sharon Krum talks to child star and trailblazing radical feminist Robin Morgan | US news". The Guardian. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Borowitz, Andy (April 21, 2008). "Goodbye Again". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Phegley, Jennifer; Badia, Janet (2005). Reading Women Literary Figures and Cultural Icons from the Victorian Age to the Present. University of Toronto Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-8020-8928-1. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt2tv2v1.

- ^ Robin Morgan's Official website Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 9 July 2010

- ^ "American Experience | Miss America | People & Events". PBS. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Morgan, Robin (1978). Going Too Far: The Personal Chronicle of a Feminist, p. 178. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-394-72612-0.

- ^ Pomerleau, Clark (2013). Califia Women: Feminist Education against Sexism, Classism, and Racism. University of Texas Press. pp. 28–29. doi:10.7560/752948. ISBN 978-0-292-75295-5. JSTOR 10.7560/752948.

- ^ Robin Morgan, "Keynote Address", Lesbian Tide, May/June 1973, Vol. 2, Issue 10/11, pp. 30–34 (quote p. 32); for additional coverage, see Pichulina Hampi, Advocate, May 9, 1973, issue 11, p. 4.

- ^ "What is a woman?". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ Stryker, Susan (2008). Transgender History. Seal Press. pp. 102–104. ISBN 9781580052245.

- ^ Meyerowitz, Joanne (June 30, 2009). How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674040960.

- ^ "Robin Morgan | Jewish Women's Archive". Jwa.org. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ ""Women's Media Center Live with Robin Morgan" Reaches 100-Show Milestone | Women's Media Center". Womensmediacenter.com. October 20, 2014. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Barnes & Noble (November 28, 2000). "Saturday's Child: A Memoir by Robin Morgan, Hardcover | Barnes & Noble®". Barnesandnoble.com. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ "Saturday's Child". The New York Times. November 26, 2000. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ "Robin Morgan: Agent of Change for Women with Parkinson's". Real Women on Health. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ Morgan, Robin. "WMC Live #33". Women's Media Center. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ "PAIR: Women's Media Center Live with Robin Morgan". Parkinson's Disease Foundation. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015.

- ^ Morgan, Robin (Fall 2014). "Women & Parkinson's Disease: Understanding this Specific Journey". Parkinson's Disease Foundation. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ "Robin Morgan: 4 powerful poems about Parkinson's and growing older | TED Talk". TED.com. September 25, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ "Tales of Tomorrow - A Child is Crying : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Video on YouTube

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Womens Media Center

- The Sisterhood is Global Institute

- Ms. Magazine

- Papers of Robin Morgan, 1929–1991 (inclusive), 1968–1986 (bulk). Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Robin Morgan Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Video produced by Makers: Women Who Make America

- Robin Morgan at IMDb

- 1941 births

- Living people

- 20th-century atheists

- 20th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American poets

- 20th-century American women writers

- 21st-century atheists

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- 21st-century American poets

- 21st-century American women writers

- Activists from New York (state)

- Actors from Mount Vernon, New York

- American abortion-rights activists

- American anthologists

- American atheists

- American child actresses

- American feminist writers

- American political writers

- American Wiccans

- American women non-fiction writers

- American women novelists

- American women poets

- American women's rights activists

- Anti-pornography feminists

- Atheist feminists

- Columbia University alumni

- Feminism and transgender

- Jewish American atheists

- Jewish American journalists

- Jewish feminists

- New York Radical Women members

- Novelists from New York (state)

- Modern pagan poets

- People from Lake Worth Beach, Florida

- Radical feminists

- Wiccan feminists

- Wiccan novelists

- Wiccans of Jewish descent

- American women anthologists

- Writers from Mount Vernon, New York

- Yippies