Herðubreið

| Herðubreið | |

|---|---|

Herðubreið, viewed from the southeast | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,682 m (5,518 ft)[1] |

| Listing | List of volcanoes in Iceland |

| Coordinates | 65°10′44.06″N 16°20′50.36″W / 65.1789056°N 16.3473222°W |

| Dimensions | |

| Area | 9 km2 (3.5 sq mi)[2] |

| Geography | |

| Location | Eastern Iceland |

| Topo map | |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | Pleistocene |

| Mountain type(s) | Tuya, composite volcano[1] |

| Last eruption | late Pleistocene[1] |

Herðubreið (Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈhɛrðʏˌpreiːθ] , broad-shouldered)[3] is a tuya and composite volcano in the northern part of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland. It is situated in the Highlands of Iceland at the east side of the Ódáðahraun ([ˈouːˌtauːðaˌr̥œyːn]) desert and close to Askja volcano. The desert is a large lava field originating from eruptions of Trölladyngja and other shield volcanoes in the area. Herðubreið was formed beneath the ice sheet that covered Iceland during the last glacial period.

Overview

[edit]This distinctive mountain has been known by its present name since at least 1300.[4] Due to the mountain's steep and unstable sides, the first definite ascent was in 1908 by Hans Reck and Sigurður Sumarliðason, despite centuries of knowledge of its existence.[2] [a] The mountain is often referred to as "The Queen of Icelandic Mountains" by Icelanders due to its beautiful shape.[7] It was voted in 2002 "Iceland’s favourite mountain".[3]

Near the mountain lies an oasis called Herðubreiðarlindir [ˈhɛrðʏˌpreiːðarˌlɪntɪr̥] with a campground and hiking trails. In former times, outcasts who had been excluded from Icelandic society because of crimes they had committed lived in the Ódáðahraun and accessed the oasis. One such outlaw was Fjalla-Eyvindur, who lived there during the winter of 1774–1775.[8]

In 2019, Herðubreið became a part of Vatnajökull National Park.[9]

Geology

[edit]Herðubreið is a basaltic central subglacial volcano that formed during the last ice age under ice at least as thick as its current prominence of about 800 m (2,600 ft).[10]: 3–4 It is usually described as a composite volcano which is the same as a stratovolcano.[1][11] It is separate from the present potentially active fissure swarms and central volcanoes nearby and is believed to be inactive. Its original magma reservoirs are believed to have been at 9–11 km (5.6–6.8 mi), and 15–18 km (9.3–11.2 mi) below the surface.[10]: 21 There is in the upper crust, between 2 and 8 km (1.2 and 5.0 mi) deep, a 10 km (6.2 mi) broad belt of shallow seismicity extending from 30 km (19 mi) to the south of Herðubreið to the mountain itself due to plate boundary spreading.[12]: 2 There is also deeper activity likely to be related to magmatic movements but perhaps this is related to the shallow volcano-tectonic seismic activity at the active Askja volcano nearby.[12]: 3 Herðubreið is a classic tuya and was quickly recognised as such after the landform was described firstly as a subglacial volcanic construct in 1947.

The eruption sequence likely started before the glaciation of the last ice age south of Herðubreið in the ridge area called Herdubreidartögl with olivine tholeiite basalt being erupted. Glaciation resulted in pressure on the magma reservoir that initially may have switched off further eruptive activity.[10]: 4 In due course a second stage in the southern part of Herðubreið melted the ice with initial olivine tholeiite lava deposition under a lake that was followed by underwater hyaloclastite mass flow deposits. This stage was not as confined by ice as the next stage and has evidence of a subaerial lava sheet,[10]: 4 and had only moderately steep ice walls below this. As the ice sheet thickened further towards the glacial maximum of 12–15,000 years ago hyaloclastite, then pillow lavas under steep-sided hyaloclastite occurred.[10]: 4 These built up until Herðubreið emerged above the lake surface, from a lake with almost vertical confining ice walls many about 800 m (2,600 ft) tall.[10]: 8 If as happened in Herðubreið's case the eruption in its last stage became again sub-aerial with a lava cap and a spatter cone or crater vent.

Accordingly the southern portion of the plateau at the top of Herðubreiðar has a deep crater, which can contain a lake in summer.[4] While by the end of glaciation, Herðubreiðar was extinct, volcanic activity resumed for a time at Herdubreidartögl to its south with fallout deposits and olivine tholeiitic lava flows in a much more spread out fashion.[10]: 4, 8

-

Snow capped Herðubreið

-

Herðubreiðarlindir

-

Stretch of Herðubreið from Möðrudalur area in 1819

-

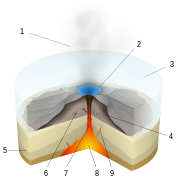

Subglacial volcano structure:1. Water vapour, 2. Lake, 3. Ice, 4. Layers of lava 5. Basement rocks, 6. Pillow lava, 7. Magma conduit, 8. Magma chamber, 9. Dyke

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Sir Richard Burton described the challenges of attempted ascent in 1871.[5] A claim was made by William Lee Howard in 1881 that he had climbed Herðubreið and this was reported in the New York Tribune with detail about the means used that are believed not to be credible.[5] William Lee Howard has also been claimed to have been the first to describe Herðubreid in sufficient detail to establish it was a volcano, with tuff at the base and lava at the top,[4] but Burton's detailed description of the mountain and its surrounds exists from a decade before.[6]: 307 [4] Although perhaps not relevant here, William Lee Howard's works have been controversial in other fields, but some of his observations of Iceland in these works do withstand the test of time. Herðubreið was climbed later in the 1930's by Olafur Jóhnsson, Edvard Sigurgeirsson, and Stefan Gunnbjörn Egilsson.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Herdubreid". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ a b Caseldine, Chris (2021). Most Unimaginably Strange: An Eclectic Companion to the Landscape of Iceland. Reaktion Books. pp. 1–324. ISBN 1789144736.: 129

- ^ a b Friðleifsdóttir, Björg Siv Juhlin (7 November 2002). "Nature and People". Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d Teitsson, Ingvar. "Herðubreið - Drottning íslenskra fjalla". International year of mountains 2002 (in Icelandic). Icelandic Environment Association. Archived from the original on 2005-02-21. Retrieved 2011-10-19. Archive.org

- ^ a b c Perkins, Henry A. (1946). "The Mountains of Iceland". ACC Publications. Archived from the original on 7 April 2024.

- ^ Burton, Richard F. (1875). Ultima Thule, or, A summer in Iceland. Vol. II. William P. Nimmo, Edinburgh. pp. 1–408 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "Var Herðubreið eldfjall og gæti hún gosið?".

- ^ Askja and Kverkfjoll: Exploring the Area, Frommer's Iceland, 1st Edition.

- ^ "Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður stækkaður: Herðubreið og Herðubreiðarlindir hluti af þjóðgarðinum".

- ^ a b c d e f g Oborn, C. (2018). Examination of a method: Testing the Kelly-Barton Method on the Herðibreið tuya, Northern Volcanic Zone, Iceland (dissertation) (Thesis). The Ohio State University. pp. 1–33. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ "Principal Types of Volcanoes". Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ a b Soosalu, H.; White, R.S. (2007). Herðubreið 2006–seismic project Scientific report (PDF) (Report). Bullard Laboratories, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge. pp. 1–4. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official Website of Vatnajökull National Park

- "Herdubreid". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- Images