Henry Salt (Egyptologist)

Henry Salt (14 June 1780 – 30 October 1827) was an English artist, traveller, collector of antiquities, diplomat, and Egyptologist.[1]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Salt, the son of Thomas Salt who was a physician and Alice née Butt, was born in Lichfield on 14 June 1780. He was the youngest of eight children and went to school in Lichfield, Market Bosworth, and then in Birmingham under where his brother John Butt Salt taught.[2] He took an early interest in portrait painting. While in Lichfield, he studied under a watercolour artist, John Glover, and in 1789, he went to London where he first studied under Joseph Farington and later under John Hoppner. After a time, he gave up portrait painting, having failed to build up a reputation.[2]

Early travels

[edit]Salt found a position with the English nobleman George Annesley, Viscount Valentia, travelling as his secretary and draughtsman, recommended by Thomas Simon Butt.[3] They started on an eastern tour in June 1802, sailing on the British East India Company's chartered ship Minerva to India via the Cape Colony. Salt explored the Cape of Good Hope, India, and the Red Sea area. Valentia came to describe Salt as a "secretary-draftsman": he was not only a companion, but also sketched the sites and scenes they encountered on their voyage.[citation needed] In 1805, Valentia sent Salt on a journey into Ethiopia (then often referred to by Europeans by the exonym Abyssinia) to meet with Wolde Selassie, Ras of Tigray to open up trade relations on behalf of the English.[2][4] While visiting there, Salt gained the respect of Wolde Selassie. He returned to England on 26 October 1806. His journey home took him through Egypt where he met the Pasha Mehmet Ali.[2] Salt's paintings from the trip were used in Valentia's Voyages and Travels to India, published in 1809. The originals of all the drawings were kept by Valentia, as also the copper plates after Salt's death. The format and style of the plates is similar to Thomas and William Daniell's work, "Oriental Scenery" (1795-1808).

Salt returned to Ethiopia in 1809 on a government mission to develop trade and diplomatic links with the Ethiopian Emperor Egwale Seyon. Upon arrival, he was unable to meet with the king due to unrest in the country, so instead he went to stay with his friend the Ras Wolde Selassie.[2] During this venture, Salt took on the side mission of verifying and correcting the information about the region reported by the Scottish traveler, James Bruce many years earlier.[4] Salt came back to England in 1811 with numerous specimens of both plants and animals. Most notable was a species of dik-dik that was previously unknown to the people of England.[2] He would go on to publish in 1814, A voyage to Abyssinia, and travels into the interior of that country, executed under the orders of the British government in the years 1809 & 1810, whose contents were on the culture, geography, customs, and topography of Ethiopia.[4] He also published a collection of drawings entitled Twenty-four Views Taken in St Helena, The Cape, India, Ceylon, Abyssinia and Egypt. He later returned and continued a friendship with the Ethiopian warlord Sabagadis.

Consul General in Egypt

[edit]Through his book and details of exploration, Salt had earned himself a name in the British government and when an opening for the Consul General of Egypt opened up in 1815, Salt was recommended to the position by Lord Valentia and appointed to be the Consul General in Egypt.[citation needed] In 1816, he arrived in Alexandria and traveled to Cairo where he would be stationed as consul.[4] Once set up in Cairo, he began to work on his mission of securing antiquities and artifacts for the British Museum. In order to successfully do this, he believed that he must first be on good terms with the ruler of Egypt, the Pasha Mohamed Ali (aka Mehemet Ali). Salt was able to foster beneficial relations between the British government and Ali acting as a middle man, negotiating deals concerning trade and territorial rights, earning him the affection of Ali. Ali was able to provide Salt with a good residence in the city and a place in his court in return for his help in negotiations.[citation needed] Salt also sponsored the excavations of Thebes and Abu Simbel, personally carrying out significant archaeological research at the pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx which earned him praise from Jean-François Champollion for his ability to decipher hieroglyphs. In 1825, Mr. Salt published, at his own expense, Essay on Dr. Young's and M. Champollion's System of Hieroglyphics; with some additional discoveries, by which it may be applied to decipher the names of the ancient kings of Egypt and Ethiopia.

Furthermore, in his tenure as Consul General, Mr. Salt devoted himself to the task of assembling a collection of antiquities, although he was hindered in every possible way by Bernardino Drovetti, who, having been dismissed from his official post, now had the time personally to supervise the search of antiquities around the country. Drovetti had great advantages over his British rival because of his thorough knowledge of Egypt, where he had been living for many years by this time, and also thanks to his close friendship with the Pasha, Muhammad Ali of Egypt. But Salt was not easily discouraged and resorting to the same methods as his rival, he surrounded himself with agents who would not stop for anything. The year he arrived in Cairo he had the good fortune to meet both Giovanni Battista Belzoni, an extraordinary individual who immediately became his main agent, and Giovanni D’Athanasi, a Greek known as Yanni, who worked for him in the Thebes area from 1817 to 1827. Thanks to his assistants, Salt was able to begin selling his artifacts in just two years. [citation needed]

Death

[edit]Henry Salt died at the age of 47 on 30 October 1827 in Desouk in Egypt. He was buried in Alexandria where he was stationed as Consul General. His paintings, papers, and artifacts he collected remain in the possession of the British Museum.[5]

Later, in 1849 Saltia was published, it is a genus of flowering plants from Yemen and Saudi Arabia, belonging to the family Amaranthaceae. It was named in Henry Salt's honour.[6]

Work and contributions to Egyptology

[edit]Collections

[edit]His first collection contained artifacts and pieces that Salt acquired from 1816 to 1818. When shipped to England and evaluated by specialists, the total value of the collection was estimated to be approximately £8000, although it would be sold for much less. Records show that the collection ended up being sold in February 1823. The sarcophagus of Seti I, a major piece of the collection was bought by the British architect Sir John Soane for £2000 and the rest was bought by the British Museum for the same price.[4]

Following the assembly of his first collection, Salt began acquiring what would be known as his second collection, containing items he collected from 1819 to 1824. While Salt's primary intention was to sell to the British Museum again, this time for a yearly pension of £600 for his service as the Consul, it would ultimately be rejected due to the price. Despite the British concerns over price, the French royalty wanted to buy the collection and display it at the Louvre, which they did in 1826 for a total of £10,000.[4]

Salt would spend the rest of his life putting together a third collection which featured his antiquities acquired from 1825 to his death in 1827. This collection was sold years after his death when an agent of his sold it to the British Museum for over £7000.[4]

Notable artifacts

[edit]- Head of Ramses II (Young Memnon) [4]

- Sarcophagus of Seti I[4]

- Head and arm of Thothmes III[4]

- Mummy of Hornedjitef [citation needed]

- Sarcophagus of Ramesses III [citation needed]

- Head and supporting Left Arm of Amenhotep III[4]

- Head and upper torso of monumental limestone statue of Amenhotep III wearing nemes.[4]

- Granodiorite seated statue of Amenhotep III.[4]

- Granodiorite statue of Amenhotep III. The statue has been restored.[4]

In popular culture

[edit]Salt was portrayed by Robert Portal in the 2005 BBC docudrama Egypt.

Gallery

[edit]-

"Ruins of the Fort at Juanpore on the river Goomtee"

-

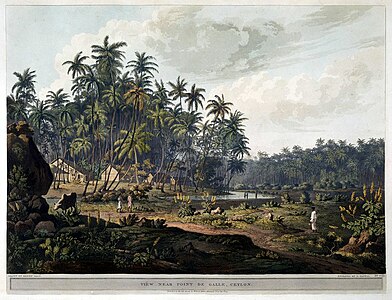

"View near Point de Galle, Ceylon"

-

"Riacotta in the Baramahal"

See also

[edit]General references

[edit]- Philosophy of Science Portal

- An excellent account of Salt and his trials and tribulations collecting antiquities in Egypt is in Maya Jasanoff, Edge of Empire: Conquest and Collecting in the East, 1750-1850, Knopf, 2005

- Manley, Deborah; Rée, Peta (2001). Henry Salt: Artist, Traveller, Diplomat, Egyptologist. London: Libri. ISBN 978-1-901965-04-9. OCLC 48506350.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur (2000). Biographical Dictionary of Modern Egypt. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-55587-229-8. OCLC 52401049.

- "Henry Salt". British Museum. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Wroth, Warwick William (1897). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 50. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ a b c d e f Manlee, Deborah (23 September 2004). "Henry Salt". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24563. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Halls, J (1834). Life and Correspondence of Henry Salt. New Burlington Street, London: Richard Bentley.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bosworth, C. E. (1974). "Henry Salt, Consul in Egypt 1816-1827 and Pioneer Egyptologist" (PDF). Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 57: 69–91. ISSN 0301-102X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Bierbrier, Morris L. (2012). Who was Who in Egyptology. London: Egypt Exploration Society. p. 484. ISBN 978-0-85698-207-1.

- ^ "Saltia R.Br. ex Moq. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science". Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

External links

[edit] Media related to Henry Salt (Egyptologist) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Henry Salt (Egyptologist) at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Henry Salt at Wikispecies

Data related to Henry Salt at Wikispecies

- 1780 births

- 1827 deaths

- 19th-century British archaeologists

- Artists from Staffordshire

- British consuls-general in Egypt

- English Egyptologists

- 18th-century English painters

- English male painters

- 19th-century English painters

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- People from Lichfield

- English male non-fiction writers

- 19th-century English male artists

- 18th-century English male artists

- Abu Simbel